The United States remains in the throes of an escalating drug overdose crisis. Data show that overdoses increased yet again in 2019, and are now soaring amid the COVID-19 pandemic, which has intensified socioeconomic vulnerabilities and wreaked havoc on service access among the most vulnerable. Every overdose death is a culmination of a long series of policy failures and lost opportunities for harm reduction.

The social determinants of health (SDOH), defined as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age, shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources,” influence risk trajectories of people who use drugs (PWUD). Structurally vulnerable PWUD—those experiencing poverty, systemic racism, homelessness, food insecurity—are more likely to die from overdoses than their more affluent counterparts.

Nonetheless, policies ostensibly aiming to reduce overdoses have not targeted these upstream factors; on the contrary, they have historically confronted substance use with moral rebuke and criminalization, paving the way for decades of aggressive policing and incarceration concentrated especially in low-income communities of color. These ‘War on Drugs’ approaches have further compounded structural vulnerabilities, increasing overdose risk, community violence, and mistrust towards public health and law enforcement.

Today, drug-induced homicide laws and disproportionate investment in policing and interdiction illustrate that the Drug War mentality is alive and well. Meanwhile, strategies that address the SDOH remain under-recognized, particularly in public policy discourse.

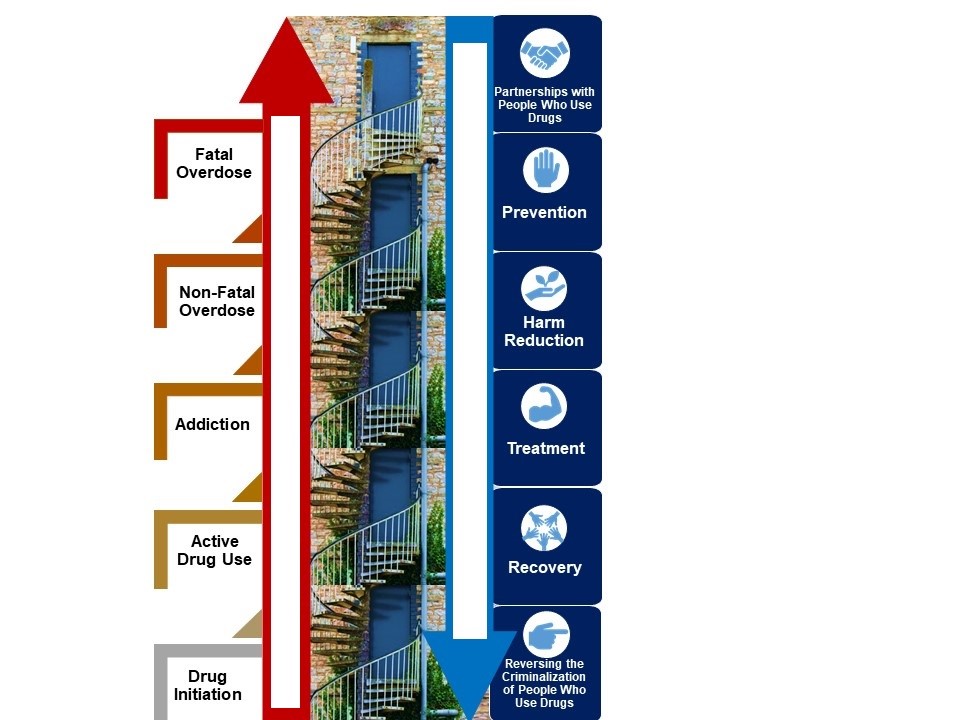

We recently published an article in Milbank Quarterly detailing the Continuum of Overdose Risk (COR) framework, developed to highlight these gaps in US policy and programming (Figure 1). The COR serves to encourage greater distinction between drug use behaviors in public health screening and prevention, and guide strategies to not only strategically de-escalate overdose risk but promote the holistic health and dignity of PWUD.

A particular goal of introducing this framework is to urge prioritization of strategies that have received comparably little attention and investment in the policy agenda: partnerships with PWUD, harm reduction, and reversing the legacy of the War on Drugs.

Figure 1. The Continuum of Overdose Risk characterizes distinct stages (red steps) of substance use that each represent opportunities to intervene to avert downstream fatalities. Six strategies to de-escalate risk are represented by blue doors along the risk continuum. The staircase analogy is employed to represent escalation and de-escalation of risk along the continuum, though individuals can skip or jump steps and risk trajectories can be nonlinear.

Factors advancing risk

The current epidemic has been characterized by three distinct waves of opioid supply and ensuing overdoses: increased availability and use of prescription opioids, a subsequent surge in low-cost heroin in illicit drug markets, and the penetration of these markets with illicitly manufactured synthetic opioids like fentanyl.

However, earlier waves of overdoses driven by heroin (1970s) and crack cocaine (1980s) that predominantly impacted urban communities of color are less acknowledged, and data highlights polysubstance and stimulant use as emerging waves in their own rite. What these past and present surges in overdose mortality share in common are their social and economic drivers, such as poverty, homelessness, and stigma, which amplify risks associated with the use of any substance.

While much focus has been placed on supply-side factors, less is placed on the social and structural risk factors operating at each stage of the continuum: drug initiation, active use, addiction, and non-fatal and fatal overdose. Microsocial factors like childhood trauma increase likelihood of drug initiation at an early age and of developing harmful patterns of use thereafter. Macrosocial factors also perpetuate risk: PWUD experiencing homelessness and police harassment drive behaviors such as public drug use and rushed injection, which in turn increase both overdose and HIV risk. Place-based factors such as income inequality, segregation, and more broadly, despair and hopelessness, are associated with fatal overdose.

Factors may operate on multiple levels: for example, incarceration increases overdose risk directly by effecting changes to individual drug tolerance, and indirectly by limiting access to stabilizing resources like medical treatment, employment, and housing.

Acknowledging these factors also allows us to de-emphasize a particular substance—or the person using that substance—as the “culprits,” and instead focus on what may potentiate or lessen harm. It is often assumed that problematic drug use inevitably follows from drug initiation, and the dominant rhetoric fails to acknowledge that many use drugs regularly without commensurate psychosocial, individual, and interpersonal harms.

Binary classifications serve to reduce all PWUD to ‘addicts’ or ‘junkies,’ removing responsibility on the part of broader society and placing it wholly on individuals who are often being systematically disenfranchised through the mechanisms discussed. Addressing this false dichotomy and adopting an SDOH approach to the current crisis must go hand-in-hand.

Strategies to de-escalate risk

Many policies are fundamentally antithetical to bolstering social and economic wellness and de-escalating overdose. PWUD are systematically marginalized through felon disenfranchisement laws, prison gerrymandering, and other efforts to deprive those with history of incarceration or drug use from political participation.

Despite the effectiveness of peer-based interventions, whereby PWUD themselves develop and deliver services, they face enduring barriers to accreditation and employment. Policymakers and academics reinforce stigma towards PWUD, failing to provide them leadership positions and remuneration for their expertise. Enacting meaningful partnerships with PWUD must be prioritized as a core tenet of comprehensive drug policy.

Prevention efforts too often focus on abstinence and interdiction. These are at best ineffective, and at worst, increase overdose risk by fueling stigma, drug market volatility and violence, and mass incarceration. Accepting that drug use will exist as it has throughout history and refocusing prevention efforts on the SDOH, and on preventing the negative consequences associated with drug use, or harm reduction, are more likely to be effective.

Evidence-based harm reduction interventions like community-based drug checking and overdose prevention sites are widely deployed in other countries and significantly reduce infectious disease and overdose risk. Nonetheless, they remain largely unavailable in the US, partly due to persisting claims that they enable drug use which are rooted in abstinence-based ideology.

Opioid agonist treatments (OAT), such as methadone and buprenorphine, reduce overdose risk and promote stabilization and recovery. However, access is hindered by factors such as lack of comprehensive insurance coverage and onerous regulatory barriers, many of which are rooted in enduring stigma, including among medical professionals, and antiquated prohibition policies. Scaling up treatment necessarily entails intervening upstream to increase overall healthcare access in low-income populations, as well as challenging notions that OAT enable drug use by simply replacing one drug with another. A broader coalition of medical, public health, and legal professionals must join PWUD in demanding access to evidence-based prevention, harm reduction, and treatment.

Enduring structural vulnerabilities pose major hurdles to PWUD seeking to sustain long-term recovery. Conflating recovery with uninterrupted abstinence, with zero tolerance of the cycles and lapses characteristic of substance use disorders, results in loss of the very resources needed to promote its longevity (e.g. making housing and employment contingent on abstinence places PWUD in precarious situations that directly threaten their recovery).

In actuality, meaningfully promoting recovery entails reversing the criminalization of PWUD to bolster access to social and economic support before, during, and after periods of possible re-engagement with drug use. Specific examples include expunging low-level drug offenses, banning employment discrimination based on substance use and incarceration history (“ban-the-box” laws), banning drug testing when it is immaterial to performing job duties, and providing access to healthcare and housing that are not contingent on abstinence. Measures like decriminalizing drug possession, retroactive expungement, and re-investing cost-savings into community-based services will help address the outsized role that the criminal legal sector plays in this crisis, and begin repairing relationships between impacted communities and the justice system.

The fissures in American society have been brutally exposed in 2020, both by the COVID-19 pandemic and deepening tensions regarding state violence towards people of color. Victims of the War on Drugs are fighting to survive at this intersection, amid social and economic marginalization, broken healthcare systems, and structurally racist policies that criminalize mental health and substance use. The time to meaningfully engage those with lived experience and critically challenge and dismantle the structures propagating institutional stigma is long overdue—further delays in adopting a justice-driven SDOH approach will only beget further fatalities.

**Feature photo by NeONBRAND on Unsplash

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Saba Rouhani, PhD, is an epidemiologist at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health whose current research focuses on social and structural determinants of health in marginalized populations. She is a recipient of the Drug Dependency Epidemiology Fellowship awarded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Ju Nyeong Park, PhD, is a faculty member in the Department of Health, Behavior, and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Park conducts research on substance use, HIV, and harm reduction approaches to health.

Ju Nyeong Park, PhD, is a faculty member in the Department of Health, Behavior, and Society at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Dr. Park conducts research on substance use, HIV, and harm reduction approaches to health.

- Share

-

Permalink