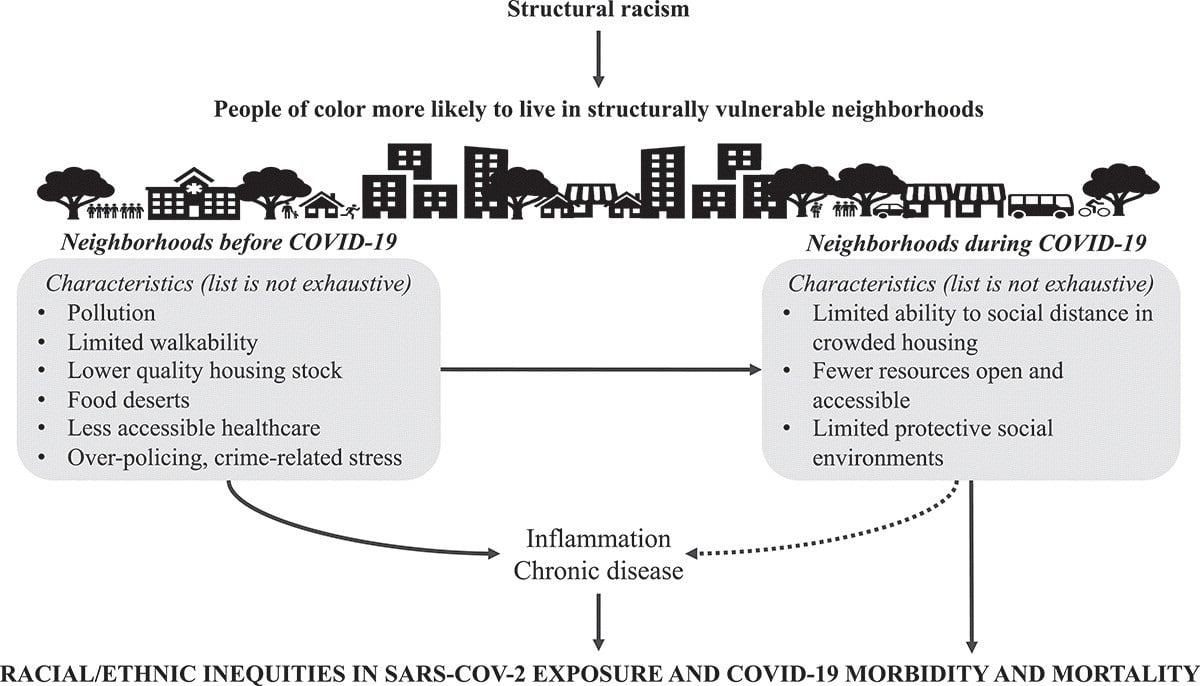

As 2021 opens with US COVID-19 cases soaring, racial/ethnic inequities persisting, and vaccine distribution ongoing, we must consider the ways in which living in structurally vulnerable neighborhoods contributes to the growing racial/ethnic inequities in COVID-19 in the United States. The following conceptual framework reflects how neighborhood environments could be acting alongside other structural forces to increase the likelihood that Black, Hispanic, and Indigenous individuals in the United States may be exposed to COVID-19, become sick, and die from severe infection.

Source: Structurally vulnerable neighbourhood environments and racial/ethnic COVID-19 inequities

Source: Structurally vulnerable neighbourhood environments and racial/ethnic COVID-19 inequities

What are structurally vulnerable neighborhoods?

First, a little context. Structural vulnerability refers to an individual’s or community’s risk for negative health outcomes, which are influenced by socioeconomic, political, and cultural/normative systems. Neighborhood-based structural vulnerability contributes to this unjust risk among individuals. Structurally vulnerable neighborhoods are themselves shaped by powerful forces meant to maintain racial/ethnic inequities in the United States, rooted in structural racism. Racial residential segregation—implemented and upheld by policies, economic institutions, the judicial system, local homeowners’ associations, and real estate organizations since the early 20th century—is an important manifestation of structural racism that continues to shape the characteristics of structurally vulnerable neighborhoods as well as the populations that are pushed towards living there.

The legacy of legalized racial residential segregation before 1968 is evident in work like the Not Even Past mapping project. Through interactive visual displays, the project compares maps of historically redlined, racially segregated neighborhoods with contemporary maps characterizing the social and economic resources available in the same neighborhoods. Across the 200 US cities mapped, many neighborhoods deemed “hazardous” or “definitely declining” the 1930s—places with large communities of color—remain racially segregated to this day, with lower life expectancy and higher rates of chronic health conditions than neighborhoods that received more favorable classifications decades earlier.

Further, historically segregated neighborhoods are now more likely to experience gentrification, which often results in the displacement of long-term residents, and disproportionately racial/ethnic minoritized populations. As a result of structural racism, communities of color are more likely than their white peers to live in structurally vulnerable neighborhoods—with poor air quality, high poverty, and greater police violence—often regardless of individuals’ socioeconomic status.

How might structurally vulnerable neighborhoods impact COVID-19 racial/ethnic inequities?

The fact that where you live affects your health is well understood, and has been summarized in popular culture with statements such as “your zip code matters more than your genetic code for life expectancy.”

Since the early days of the pandemic, researchers and practitioners have recognized the potential for neighborhoods to similarly impact COVID-19 outcomes and disproportionately burden communities of color living in structurally vulnerable neighborhoods. Current pandemic research has found evidence of disproportionate burden of COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths in areas that have lower socioeconomic status and poor housing conditions.

Though research is ongoing, zip code- and county-level studies have found relationships between COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, and deaths, and places with:

- Greater racialized economic segregation;

- Greater racial residential segregation;

- Larger populations of communities of color; and

- More anti-Black bias.

These studies suggest that racism may be playing a significant role in the pandemic in general and COVID-19 racial/ethnic inequities in particular.

In our recent commentary, we theorized that structurally vulnerable neighborhoods prior to the pandemic may have diminished opportunities for physical activity and healthy food access and may also be sources of chronic stress; both of these realities may increase residents’ risk for chronic conditions associated with greater COVID-19 morbidity and mortality (e.g. obesity, type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease).

In addition, there are several ways that structurally vulnerable neighborhoods and their residents may be disproportionately affected by interventions to prevent the spread of COVID-19. For example, in neighborhoods where more individuals are essential workers, strict adherence to shelter-in-place ordinances is not feasible. Residents in lower income neighborhoods may not have the privilege of being able to work-from-home and maintain their livelihoods. Additionally, in neighborhoods where families are more likely to live in crowded housing, residents may not be able to observe physical distancing recommendations as easily. These realities in turn increase risk of exposure to the virus for all residents.

Other potential pathways have yet to be investigated, including over-policing of communities of color to enforce shelter-in-place ordinances, or the closing of sites of social support (e.g. churches, community centers), thereby limiting access to potential protective factors. Attention must be paid as the pandemic continues and as we look to building more supportive communities moving forward.

Moving forward

Alongside ongoing quantitative research, we must engage in qualitative and community-based participatory research at increasingly local geographic levels and further investigate the pathways through which structurally vulnerable neighborhoods influence individuals’ risks and racial/ethnic inequities in COVID-19. And this research must ultimately support action. Place-based community development at the local level, and a Health-In-All-Policies approach at the city, county, state, and federal levels, are strategies to translate research into visible change that center equity, recognize structural racism as a root cause of inequity, and support the transformation of structurally vulnerable neighborhoods. The COVID-19 pandemic has shown the world just how pervasive, persistent, and egregious racial/ethnic health inequities remain in the United States, and ensuring that neighborhoods are places where all residents can truly thrive is one important step towards a more equitable future.

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Rachel L. Berkowitz, DrPH, MPH, is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow in Health Equity & Implementation Science through University of California, Berkeley, and the Sutter Health Center for Health Systems Research. Her research projects involve assessing the ways in which neighborhood contexts influence and drive racial inequities in birth outcomes and maternal outcomes, evaluating pilot efforts to collect and utilize social determinants of health information in clinical settings, and examining the impacts of changes during the COVID-19 pandemic on the experiences and outcomes of patients and providers.

Xing Gao, MPH, is a doctoral student in Epidemiology at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health. Using her training in Geography and Epidemiology, her research centers at the intersection of race, place, and health: she investigates how neighborhood conditions, influenced by broader contexts of structural racism and concentrated disinvestment, contribute to racial/ethnic health inequities that are unevenly distributed across space.

Xing Gao, MPH, is a doctoral student in Epidemiology at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health. Using her training in Geography and Epidemiology, her research centers at the intersection of race, place, and health: she investigates how neighborhood conditions, influenced by broader contexts of structural racism and concentrated disinvestment, contribute to racial/ethnic health inequities that are unevenly distributed across space.

Eli K. Michaels, MPH, is a 4th-year PhD candidate in Epidemiology at the UC Berkeley School of Public Health. Her research is broadly focused on measuring racism and estimating its effects on racial health inequities in the United States. She is particularly interested in using big data to measure the ambient social climate as it pertains to race and racism, exploring the interplay between structural and cultural racism, and examining biopsychosocial pathways to health.

Mahasin S. Mujahid, PhD, MS, is an Associate Professor of Epidemiology and the Aldous Lillian E. I. and Dudley J. Aldous Chair at UC Berkeley School of Public Health. She employs interdisciplinary and community-based approaches to investigate racial/ethnic and place-based health disparities, and her primary area of research examines the role of neighborhood environment in cardiovascular health. Dr. Mujahid’s research, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, has been published in leading public health and medical journals nationally.

Mahasin S. Mujahid, PhD, MS, is an Associate Professor of Epidemiology and the Aldous Lillian E. I. and Dudley J. Aldous Chair at UC Berkeley School of Public Health. She employs interdisciplinary and community-based approaches to investigate racial/ethnic and place-based health disparities, and her primary area of research examines the role of neighborhood environment in cardiovascular health. Dr. Mujahid’s research, funded by the National Institutes of Health and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, has been published in leading public health and medical journals nationally.

- Share

-

Permalink