I can’t breathe! This has become an all too familiar cry for many African Americans who everyday struggle to breathe in a society suffocated by systemic racism and entrenched inequities. They struggle to live in a society that has intentionally erected barrier after barrier intended to weaken their bodies and hasten their deaths. What we have is the perfect storm for a disaster—a serious health crisis, an inequitable method of health delivery, millions of uninsured and under-insured people, an uneven and politically charged approach to dealing with the pandemic, police brutality, and other injustices, an upcoming election, and some of the most vulnerable people on the front lines keeping our country going.

Since January 2020, the U.S. has led the world in the number of deaths attributed to the coronavirus; more than 100,000 people have died, and morbidity and mortality rates continue to rise. Today, nearly a quarter of the total deaths are African American, which is a startling fact given they are only 13% of the United States population. Data have demonstrated that racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately impacted by the disease—a fact that further solidifies the disparate nature of race and ethnicity relative to one’s health and the inequities in healthcare that these individuals experience. For more than 400 years, differences in health outcomes between whites and blacks have been part of the American landscape, so entrenched in our society that many people fail to recognize that our nation’s health, including its health inequities, is not an organic outcome.

Examining the Roots of Health Inequalities: The Political Determinants of Health

We know that the underlying factors such as cancer, asthma, heart disease, diabetes, lung disease, and other chronic diseases that put racial and ethnic minorities at greater risk from dying from COVID-19 have been striking disproportionately within communities of color for centuries in America. The inequities that predate COVID-19 did not suddenly become inapplicable. African Americans, Native Americans, Latinx Americans, Asian and Pacific Islander Americans still contend with neighborhoods that are largely devoid of health-sustaining and health-protective resources, and they still contend with the political determinants or drivers that created, perpetuated and exacerbated these health inequities. COVID-19 is NOT striking all equally, because our economic and social policies have not been benefitting all equally!

A national crisis tends to magnify inequities in our society. Like past epidemics or pandemics, the COVID-19 pandemic negatively impacts and further disadvantages lower socioeconomic communities, racial and ethnic minorities, and immigrant communities the worst. What these past crises have shown us is how one political determinant after another resulted in a continual tightening of a chokehold on these disparate communities and the eventual disaster that brought to light the inequities plaguing them. High obesity rates, diabetes, maternal mortality, depression, and many other health issues can be firmly linked back to political action or inaction. By understanding the political determinants of health, their origins, their impact, and interconnection with the social determinants of health, we will be better equipped to develop and implement actionable solutions to close the health gap.

Getting from Social Determinants of Health to Political Determinants of Health

It is true that the air pollution, climate change, toxic waste sites, unclean water, lack of fresh fruits and vegetables, unsafe, unsecure, and unstable housing, poor-quality education, inaccessible transportation, lack of parks and other recreational areas, and other factors play an outsized role on our overall health and well-being. They increase our stress, expose us to harmful elements, and limit our opportunities to thrive. These social determinants of health play an outsized role in these human-made pre-existing inequities, but underlying each one is a political determinant that we can no longer ignore.

Too often we stop at the social drivers of inequities, failing to dig even further to see the depths of the problem and understand its root causes and distribution. As a result, we miss the link between social determinants of health and their political roots. Consider, for example, the studies linking higher rates of asthma in communities of color to greater air pollution, which other studies have shown is linked to bus depots, highways, parking lots and other social determinants of health that exist within these communities. To get to the root cause of these inequities we must venture further upstream to understand how these social determinants of health were allowed to occur or not occur in the first place.

This pandemic demonstrates the inconvenient and harsh truth about the impact of social determinants of health, and how collectively these factors significantly contribute to our society’s health inequities. It shows the compounding effect of political determinants over personal responsibility. No matter how much African Americans, Native Americans, Native Hawaiians, Latinx Americans, Pacific Islander Americans, and individuals of lower socioeconomic status try to act responsibly, structural, institutional, and interpersonal obstacles hinder them. Beneath these communities’ notice, political determinants have pulled and continue to pull strings that prevent them from achieving their optimal health and full potential, leading to what Dr. Arline T. Geronimus has coined “weathering,” or accelerated aging, which increases these communities’ rates of chronic diseases.

Behind virtually every health disparity and subsequent death, especially during this time of COVID-19, there were specific and insidious political determinants of health that led to the person’s premature death. The good news is that structural barriers and the resulting inequities are not permanent, but it will take greater action and collective agreement from individuals committed to stomping out inequities to formulate and execute the strategies and policies to overcome them. Unless we do these things, we will continue to suffocate from systemic racism and entrenched inequities, and we will make little progress in keeping the determinants of our health in check. As we move forward in stomping out racial inequities in America, it is worth remembering that health equity begins and ends with the political determinants of health. Only then will we be able to move the United States from its partial commitment to equality to a full commitment to equality.

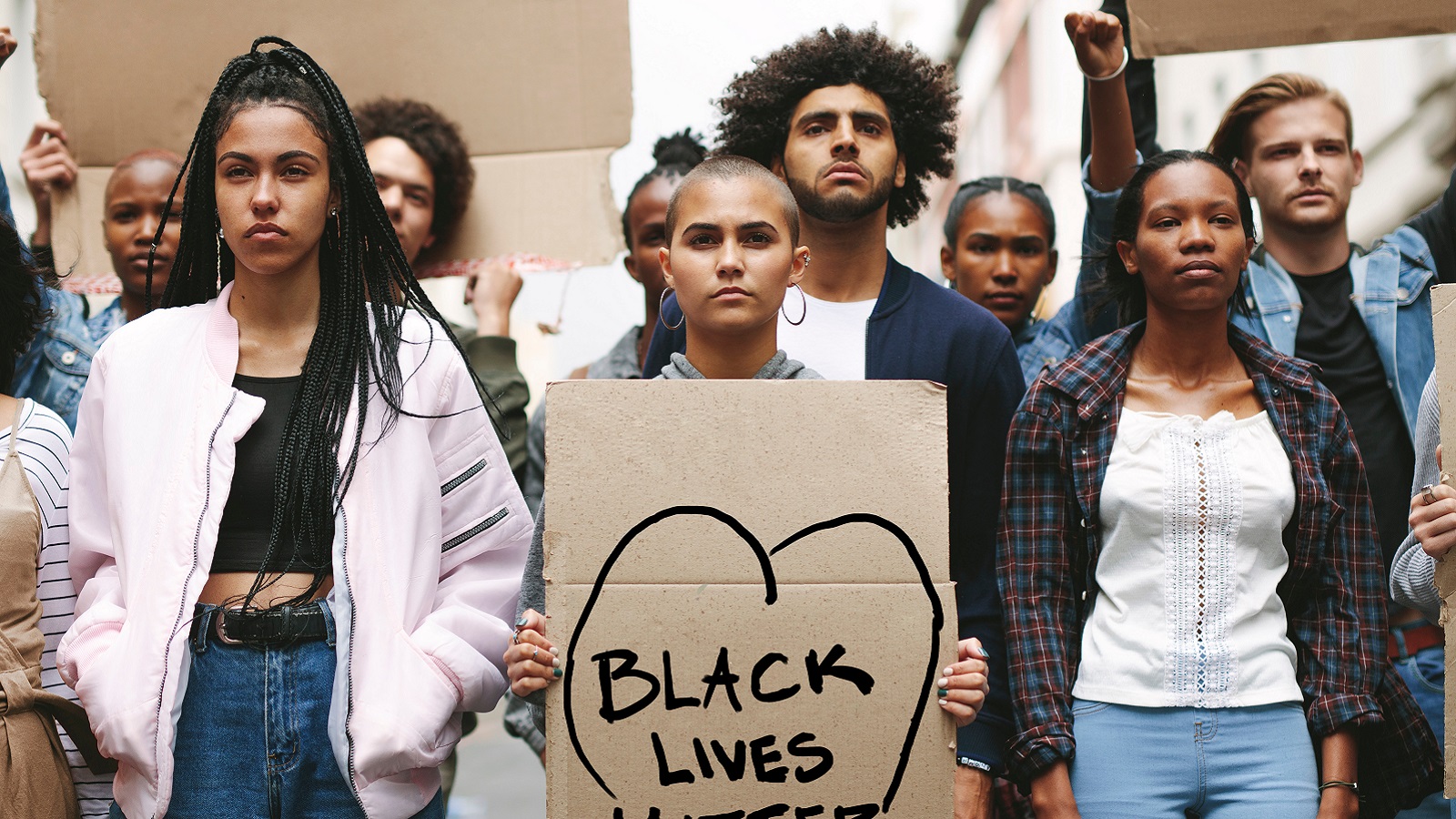

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to the Center's bi-weekly newsletter

Daniel E. Dawes, JD, is a professor of health law and policy, the Director of the Satcher Health Leadership Institute at Morehouse School of Medicine, and co-founder of the Health Equity Leadership and Exchange Network (HELEN). Professor Dawes is the author of two books on the topic of health equity and racial health disparities published by Johns Hopkins University Press: 150 Years of Obamacare and The Political Determinants of Health.

- Share

-

Permalink