A humbling sense of medical uncertainty. Tensions between public health concerns versus economic consequences for shuttered businesses. Public recognition of heroic healthcare workers, especially nurses. Concern over the standards used to gauge therapeutic efficacy. Even homemade masks. Such tensions and tropes of course color our contemporary experience of the COVID-19 pandemic, but they likewise appeared throughout the 1918 influenza pandemic and its aftermath. A look backward at the 1918 pandemic, especially in Boston, reveals shared commonalities, at the same time that it demonstrates the critical importance of local context and the opportunity for such crises to effect enduring change.

It is hard to recapture just how unnerving the 1918 pandemic appeared to contemporary clinician-scientists. Pathologist William Welch, the first dean of the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and emblematic of the rise of scientific medicine in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was reportedly shocked by what he saw in traveling at the government’s request to examine the devastation at Camp Devens in Massachusetts. As reported by Rufus Cole, who accompanied his former chief and who was by then himself Director of the Hospital of the Rockefeller Institute in New York:

When the chest [of a recently deceased patient] was opened and the blue swollen lungs were removed […] and Dr. Welch saw the wet, foamy surfaces with real consolidation, he turned and said, “This must be some new kind of infection or plague,” and he was quite excited and obviously very nervous. It was not surprising that the rest of us were disturbed, but it shocked me to find that the situation, momentarily at least, was too much even for Dr. Welch.

Indeed, as described by Warren Museum Curator Dominic Hall, Welch would ask Harvard pathologist Burt Wolbach to help determine the nature of the disease through such lung pathology, and within several years, Wolbach would contribute to the dismissal of the notion of the bacterial cause of influenza (the carefully preserved lung specimens remain at Harvard’s Warren Anatomical Museum to this day).

The course in Boston, as elsewhere and as reported in the University of Michigan’s terrific Influenza Encyclopedia, was tied up with the transport routes and vulnerabilities generated during the ongoing war. The first cases appeared on the military’s receiving ship at Commonwealth Pier at the end of August, spreading to Boston’s civilians by early September. By September 26th, Boston’s schools had been closed, and Boston Health Commissioner William Woodward, after prodding by the governor, ordered the closure of the city’s theaters, movie houses, and dance halls. Temporary hospitals were quickly established and filled, though given that many physicians and nurses had been called to military service, healthcare delivery would be supplemented by the efforts of Boston and Cambridge schoolteachers, newly released from teaching duties.

Harvard Medical School (HMS) and its newly established teaching hospital, the Peter Bent Brigham (PBBH), likewise responded, in some dramatic ways. Fourth year HMS students, working under future Nobelist George Minot, examined the cadets at the Students’ Army Training Corps housed at Harvard College, ensuring the isolation of those appearing infected. At the PBBH, as reported at the time by Physician-in-Chief Henry Christian and as recently unearthed by Brigham & Women’s Hospital archivist Catherine Pate, it was indeed all-hands-on-deck:

For a number of weeks practically the entire hospital was given over to the care of influenza cases. Every medical bed and half of the surgical beds were occupied by influenza cases. In the remaining beds were concentrated such surgical and medical cases as must needs remain in the hospital or be admitted as emergency cases. The Surgical Staff loaned to the Medical Staff four of their house officers to care for influenza cases, and very generously the surgeons curtailed their work to a minimum. Without this help from the Surgical Staff we would have been unable to meet the needs of the situation.

Concerns regarding the manner of contagion and the 1918 equivalent of personal protective equipment (PPE) were clearly evident:

In handling influenza patients all who came in contact with them were gowned, capped, and masked, and care in washing hands was insisted on. Our present knowledge of influenza is too inadequate to make certain how far these precautions are necessary. At present they seem wise. Consideration of the infection among our nurses and doctors indicates that they acquired the disease not from patients in the wards but from contact with one another, or with maids, or with outside friends just developing the disease; in other words, the disease is most contagious during the incubation period.

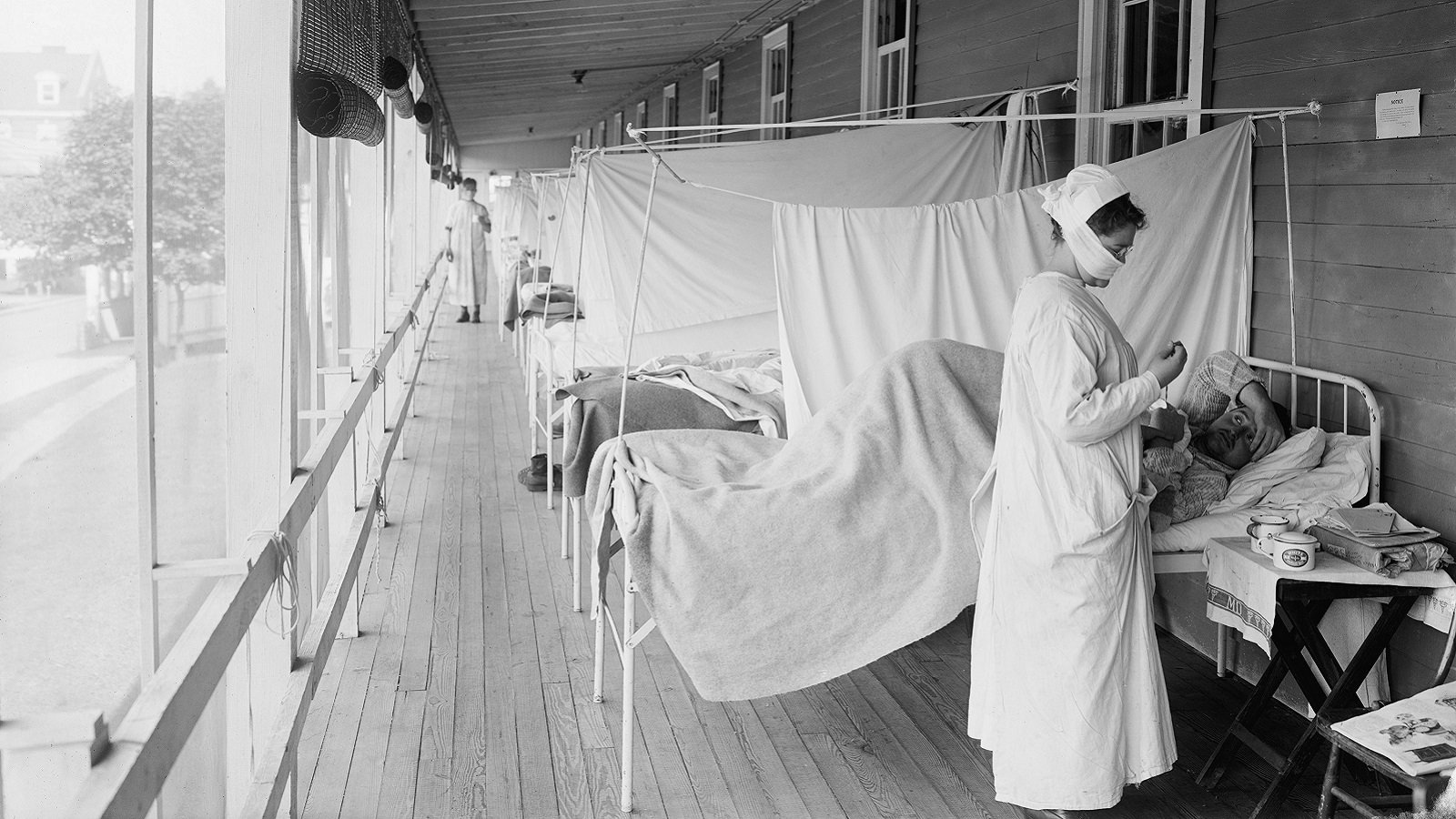

And skillful and heroic efforts, especially among the nurses, were apparent and appreciated:

Our nurses did most excellent work during the epidemic. The numerous cases of the disease among them made it necessary for the well ones to work with redoubled energy. Pupil nurses had to replace graduate head nurses as the latter fell ill, and so had thrust upon them much responsibility. Nurses could not but feel the grave danger they ran in handling a disease which evidently in some part of its course was extremely contagious and which was causing a high toll of deaths right under their eyes. There was no faltering; each did her duty and carried out her work efficiently.

The flu pandemic’s course in Boston was more compressed than that of COVID-19 today. By mid-October 1918, influenza seemed to have peaked. On October 19th, closure orders were reversed, and on October 21st, schools were reopened. Altogether, nearly five thousand Boston residents were reported to have died from the flu and its associated pneumonia in the fall of 1918, making it the third hardest hit city (per capita) in the country, behind only Pittsburgh and Philadelphia.

This leads to a final question: What was the lasting impact of the 1918 pandemic, and what will be the lasting impact of our own? One of the less appreciated aspects of the 1918 influenza was its ultimate role in transforming clinical research. By the 1910s, a handful of researchers were applying more sophisticated approaches to clinical trials, alternating every other patient to a treatment and comparing outcomes. In the aftermath of the flu pandemic, the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company lost $24 million in excess death benefits; the life insurance company was concerned about the status of claims made about treatments directed towards secondary bacterial pneumonia that seemed to be the actual cause for most deaths among influenza patients. Not knowing when the next pandemic would hit, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company funded perhaps the first multi-institutional controlled clinical trial of anti-pneumococcal antiserum. “Alternate allocation” studies were performed on the Harvard Medical Unit of Boston City Hospital (led by then-fledgling investigator Max Finland, at the start of a monumental career in infectious diseases) and at Bellevue and Harlem Hospitals in New York, finding that antiserum seemed to work against certain types of pneumonia. Concerns over how such “alternate allocation” was implemented (and how it could be cheated by well-intentioned investigators) would ultimately play a key role in the switch, by the late 1940s, to concealed randomized allocation as the lynchpin of what would come to be known as the randomized controlled trial.

As David Jones recently wrote, it is certainly easier to trace such relationships from the perspective of the historian than it is to predict them moving forward. What, beyond the fundamental shift in the role of telehealth, will be the long-term consequences of the current pandemic? Optimists hope and advocate for increased attention to the social determinants of health and health inequities; an increased focus on caregiving as a fundamental, moral activity in home and institutions alike; and for us to re-consider how primary care is organized, funded, and implemented. The COVID-19 pandemic has been humbling in so many respects, but one hopes that future historians can look back on the positive changes—or even fundamental shifts—we’ve engendered in response.

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to the Center's newsletter

--

Scott Podolsky, MD, is a Primary Care Physician at Massachusetts General Hospital, Professor of Global Health and Social Medicine at Harvard Medical School, and Director of the Center for the History of Medicine at the Countway Medical Library. He is the author of Pneumonia before Antibiotics: Therapeutic Evolution and Evaluation in Twentieth-Century America (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006) and The Antibiotic Era: Reform, Resistance, and the Pursuit of a Rational Therapeutics (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2015). He first came across Rufus Cole's harrowing first-person depiction of the devastation wrought by influenza at Camp Devens while he was burrowing in the Rufus Cole papers at the American Philosophical Society, researching his pneumonia book.

- Share

-

Permalink