Over the past few decades in the field of education, we have engaged in expensive, energetic and well-intentioned reform to our systems of schooling. These changes, including accountability, curriculum and instruction, have been aimed at achieving a very ambitious goal, summed up in the titles of our two most recent federal policy initiatives: “No Child Left Behind” and “Every Student Succeeds.” Sadly, the results of these reforms at the local, state and federal levels have been modest. There have been pockets of success in individual schools and districts, and some states have earned widespread acclaim for boosting averages and raising the achievement floor. Overall, though, here’s what we see on the national level: deep, persistent achievement gaps that remain, similar to the gaps that existed when this round of education reform was launched in the early 1990’s.

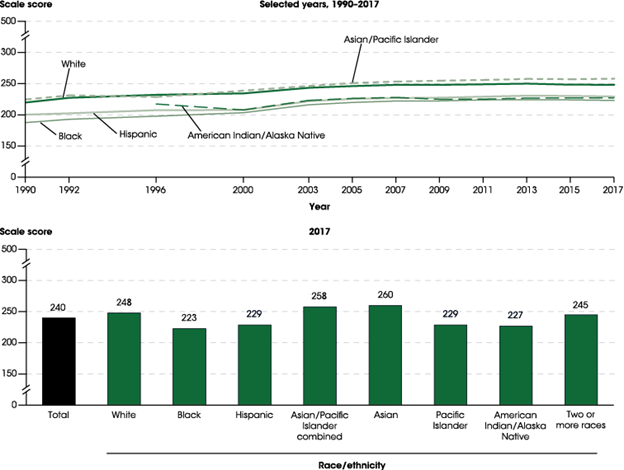

Here’s one illustrative snapshot of disaggregated achievement scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (i.e. the Nation’s Report Card) displayed over the years of reform:

Figure 11.1. Average National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) mathematics scale scores of 4th grade students, by race/ethnicity: Selected years, 1990–2017

SOURCE: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), selected years, 1990–2017 Mathematics Assessments, NAEP Data Explorer. See the Digest of Education Statistics 2017, Table 222.10.

There are an infinite number of such illustrations, including many that track the performance of low-income students who also fare poorly when compared to the top performing subgroups.

The unavoidable conclusion is that education has failed to meet Horace Mann’s (19th century education leader regarded as the founder of modern, public education) noble ambition that a common school—that is, a public education system open to all—would be “the great balance wheel of society,” the equalizer, the ticket to creating a genuine American meritocracy. As it has been throughout history and still remains now, there is a very strong correlation between children’s socioeconomic status and their educational achievement. In other words, the best predictor of educational success is the income and wealth of an individual’s family. This is not how America was intended—rather, in America, everyone should have a fair chance to succeed.

We live in an era of enormous and growing disparities of income and wealth, a society characterized by decades of steadily declining social mobility. In the midst of this inequitable ecosystem, schools are expected to overcome the pervasive, gross inequities of students’ living conditions to equally prepare all children with the skills needed to succeed in our 21st century high-skill, high-knowledge economy. And to top it off, schools are inadequately, and often unfairly, funded. They are simply not given the capacity to achieve the astronomical goals set by policymakers. They don’t even have sufficient time: schools consume only 20% of a child’s waking hours between kindergarten and 12th grade. As it turns out, schools are a relatively weak intervention in the lives of children. Though schools make a life-changing difference for some who defy the odds, children in racial, ethnic or low-income subgroups are usually caught in the achievement gaps and struggle to succeed.

Within the fields of public health and medicine, many leaders have sharply focused attention on the social determinants of health, the underlying forces that ultimately shape health. The basic contention in the “social determinants” analysis is that health outcomes could be significantly improved if we invest in public safety, supportive housing, food security, education, public transportation, employment opportunities, and clean air and water.

Likewise in education, the same factors contribute to success. Regardless of how much we reform and optimize schools, if students don’t show up, or show up laboring under toxic stress, then even the best academic programs won’t succeed in improving these children’s outcomes. The problem is schools do not have the expertise, time or authority to address these problems. They are already overwhelmed.

As a society, our healthcare and education systems invest too much in treating the symptoms of living conditions, like poverty, that should not be allowed to exist. If we shifted our investments to mitigating the oppressive policies and practices that create poverty, we would certainly improve health and education outcomes for all people, including our most vulnerable populations.

The challenge, it seems to me, is how our respective education and healthcare communities can come together to make common cause in attacking the systems that cause poverty, family instability and widespread suffering. One clear fact is that we cannot do this by ourselves. We must raise our voices, together, to command the urgent attention of our leaders to collectively and comprehensively address the social determinants of health and education. To gain the attention of our leaders, we must stand up, speak out and address their moral and economic interests. Many will listen because Americans care deeply about children and health.

We can start this work by building local demonstrations, mechanisms like citywide, children’s cabinets to bring together grassroots and grasstops leaders throughout the community to address the needs of our youth. Irrespective of the approach we take, we now have a moment in the national consciousness which can be shaped into a movement. With thoughtful strategy, we can build this movement to eradicate the social determinants that constrain our respective professions and undermine the lives of our fellow citizens.

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to the Center's newsletter

.jpg?width=150&name=Paul%20Reville%20(002).jpg)

Paul Reville, Ed.M., is a Professor at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where he leads the Education Redesign Lab. He is a former Massachusetts Secretary of Education.

- Share

-

Permalink