The COVID-19 crisis continues to expose deep vulnerabilities in the U.S. healthcare system—from the dearth of personal protective equipment to the lack of surge capacity to fragile hospital financials. And yet many of the most concerning issues laid bare are ones that originate outside the system.

Some have called this coronavirus the “great equalizer,” as all of us—in every corner of the country—are at risk. But although pathogens might not discriminate, our society certainly does. And with each passing day, patterns in COVID-19 morbidity and mortality are revealing the many underlying injustices that have long led to disparate health outcomes.

For centuries, health crises have disproportionately impacted the poor, the sick, and the most marginalized in our society. The current pandemic is no exception. Across the United States, your experience with the novel coronavirus has a great deal to do with who you are.

People of color, in particular, are bearing the brunt of this disease. Black Americans are hospitalized for coronavirus-related illnesses at higher rates than any other racial or ethnic group—and they account for one in four coronavirus deaths, despite being just 13% of the population. Latinos are also four times as likely to be hospitalized for COVID-19 than white people. Native Americans, too, face a similarly disproportionate risk.

The fact is, systemic discrimination and inequality have a tremendous impact on who contracts this virus, what type of care (if any!) they’ll have access to, and how severe their case will be.

First, there are disparities in risk exposure. By now, most of us are aware that physical distancing is our best defense against this virus. And yet, the ability to keep our distance is a privilege not everyone enjoys. Black and Brown Americans make up a disproportionate number of essential workers, such as home health aides, grocery store clerks, and bus drivers, who do not have the luxury of doing their jobs from home. And, as a recent study of New York City subway ridership by neighborhood illustrates, they are also more likely to ride public transportation to those jobs, increasing their risk of exposure.

And when they do get sick, people of color often receive poorer medical care. Although the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has helped to close the gap in healthcare coverage, people of color are still significantly more likely to be uninsured. And even when they have insurance, racial and ethnic minorities—African Americans in particular—often receive lower-quality care than white patients do. That’s true even when controlling for socioeconomic factors like income and education.

But what happens inside the healthcare system itself is only a small part of the story. Research shows that 80-90% of a person’s overall health is determined by factors outside of clinical medical care. A growing body of literature confirms that social determinants, or the conditions in which we are born, live, work, and play, are the key drivers of these health outcomes—and inequities.

Communities of color face vast disparities in educational opportunities, income, and intergenerational wealth. On the whole, they have worse access to healthy food, green outdoor spaces, and housing security. They are less likely to have paid sick leave. And all of these deeply embedded inequities have significant consequences for overall health and well-being.

That is to say nothing of the impact of racism itself. In addition to the consequences of structural discrimination, it is well documented that experiencing racism has adverse consequences on health. Chronic stress from discrimination can lead to “wear and tear” on the body, which in turn can cause a range of adverse health outcomes, from high blood pressure and heart disease to immunodeficiency and accelerated aging. It in part explains the alarming maternal and infant mortality rate among Black mothers.

These factors contribute to underlying health conditions—like asthma, diabetes, heart disease, and hypertension—that make viruses like COVID-19 all the more dangerous. Look no further than the impact of air pollution. Black Americans, for example, are disproportionately likely to live near a polluting facility like a factory or a refinery—and farther from air quality monitoring sites. Black children had a 500% higher death rate from asthma compared to white children. And now, we’re seeing a link between long-term air pollution exposure and COVID-19 fatalities.

A nationwide study conducted by the Harvard Chan School of Public Health recently found that counties with higher pollution levels—the kind from car fuel combustion, refineries, and power plants—have more coronavirus-related hospitalizations and deaths. For example, a person who has lived for decades in a county with high levels of fine particulate air pollution is 8% more likely to die from COVID-19 than someone who lives in a place with one less unit (one microgram per cubic meter) of such pollution.

The underlying societal factors that have led to such disparities are as entrenched as they are unacceptable. That said, the outcome is not preordained. As fall approaches and COVID-19 cases continue to climb, there are things we can and must do immediately to reduce the spread of the virus and protect those who are most vulnerable.

Above all, we need robust data. That includes the racial and ethnic breakdown of who is contracting—and being treated for—this disease. We simply cannot address this problem unless we understand the scope. Unfortunately, the Trump Administration’s new directive to hospitals to divert such data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will make accurate information that much harder to come by.

We in public health must also continue to push for accurate data. And we must use it to shine a light on disparities—and help health providers implement solutions. That includes providing communities with credible, culturally competent information on how to protect against the virus and how and when to seek treatment. It also means working with health systems to implement anti-bias training for providers and reduce barriers to quality care.

This, of course, is just the beginning. In the long run, what is happening today must serve as an urgent wake-up call to the underlying inequities that have long hurt the health of communities of color. Righting these wrongs will require a range of policy interventions—from affordable housing and paid sick leave, to environmental justice and universal healthcare. And it will require us to confront and address the longstanding racial biases that pervade American society—not just in healthcare, but in all areas of daily life.

That will be a great equalizer, and it will save countless lives.

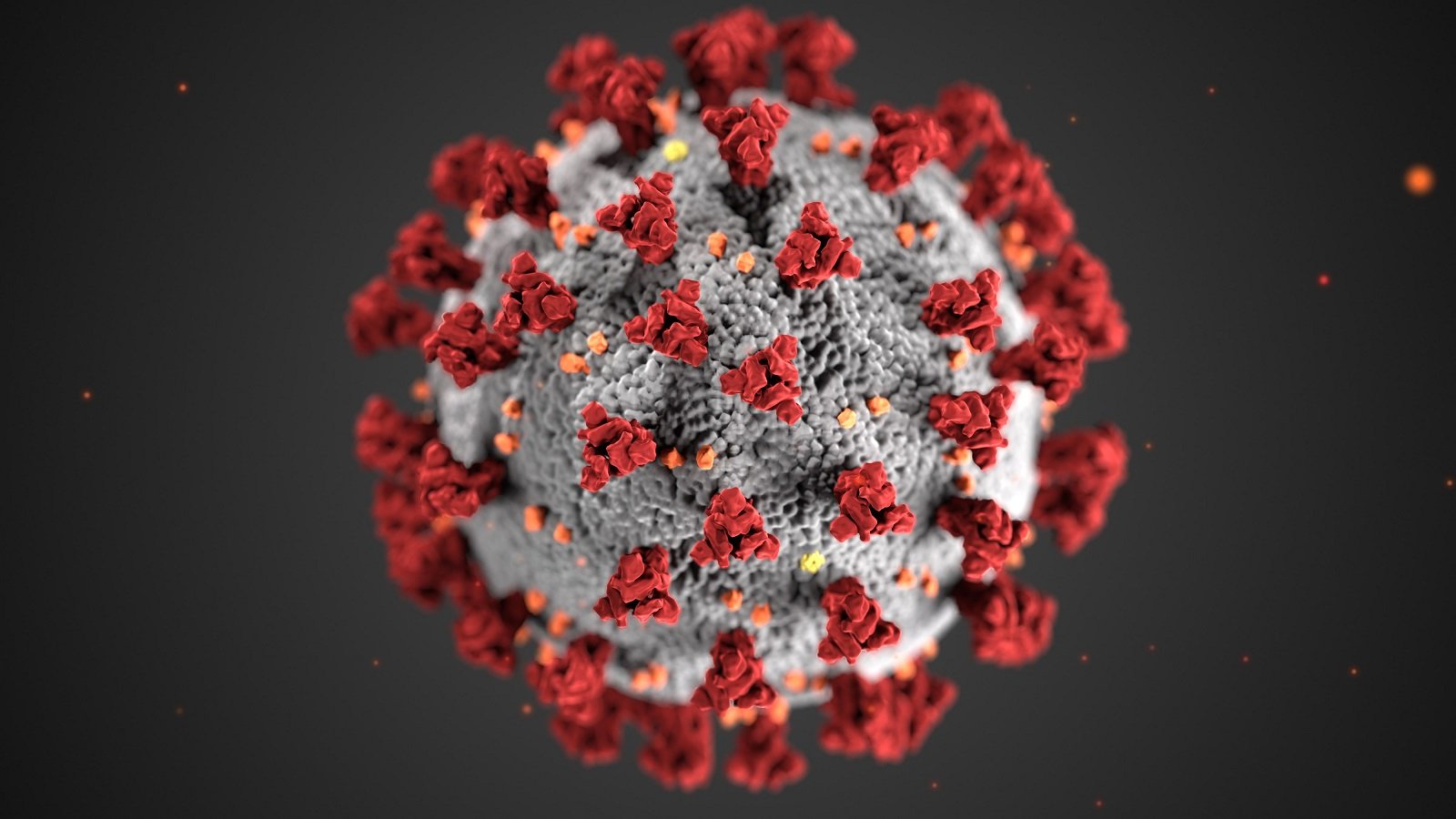

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Michelle A. Williams, ScD, is an epidemiologist and dean of the faculty, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. She is the Angelopoulos Professor in Public Health and International Development at the Harvard Chan School and Harvard Kennedy School.

- Share

-

Permalink