In the Show-Me State, a wave of rural hospital closures began in the 2010s and continued into the next decade, recently hitting Boonville, Missouri, with a closure in January 2020. In addition to the seven Missouri hospitals that have closed since 2010, multiple hospitals in neighboring states (Arkansas, Kansas, and Tennessee) have also shuttered their doors.

Even among the rural hospitals that do remain open, many still close their labor and delivery wards, citing lost revenue, as many rural areas are decreasing in population but increasing in age. This has led many birthing people in rural Missouri to drive more than 100 miles (sometimes crossing state lines) for prenatal care and birth. This loss of access to care has led to health disparities nationwide that are especially critical in rural Missouri. The ten counties with highest rates of maternal mortality are located in rural areas of the state, according to the Rural Missouri Biennial Report of 2018-2019.

Despite such staggering rates, there are those who are actively working to improve rural health quality and access, such as Farrah McSpadden, MD, an obstetrician and gynecologist (OB/Gyn) in Poplar Bluff, Missouri. McSpadden’s clinic is a part of Missouri Highlands Health Care System, a community-based federally-qualified primary care system funded by the HRSA Health Center Program. As Missouri’s Medicaid expansion has continued to falter, clinics like these have channeled federal funding to serve underinsured and uninsured populations in rural areas and improve patient outcomes.

Unlike other Missouri labor and delivery wards that are closing, the team at the Missouri Highland’s Women’s Clinic is expanding. McSpadden currently works alongside two nurse practitioners to serve a growing patient panel. They will be onboarding a second OB/Gyn in October, and they would like to hire a midwife as well (although midwives are difficult to find in Southern Missouri). The clinic has access to sonographers, a laboratory, and connections to the twelve other Missouri Highlands clinics that hold behavioral health, dentistry, and primary care services for patients.

Like many rural healthcare providers, McSpadden hails from the area she practices, and she knows the ins and outs of the patient population. Over the years, she has seen the harsh effects of the opioid and IV drug use epidemic in Missouri — and the negative impact of the epidemic on maternal and infant health. Currently, patients from her area must drive several counties away to be prescribed Subutex and Methadone. This distance may be even farther for pregnant patients, who often face providers who may be hesitant to prescribe to them. In an effort to combat this barrier to care, several Missouri Highlands providers have obtained a Data 2000 waiver, which will allow the center to prescribe these medications in-house. McSpadden is in the process of obtaining her own waiver so that she can provide a similar service to her own patients.

Utilizing nurse practitioners is one way to address the rural physician shortage. The Missouri Primary Care Needs Assessment of 2020 reported that 72 of Missouri’s 114 counties lack an OB/Gyn. To improve access, the Missouri Board of Registration for the Healing Arts allows physicians like McSpadden to be 75 miles away from a nurse practitioner (NP) trained in the Women’s Clinic. McSpadden and the NPs at the Women’s Clinic proctor primary care NPs on foundations of obstetric and gynecological care (such as annual examinations, pap smears, IUD or nexplanon insertion and removal), thereby empowering the primary care NPs to provide for rural populations who have limited access to OB/Gyn care. Following training, the NP works under the license of another physician, usually a family medicine physician, but they may consult McSpadden if patient complications arise. This is a game-changer for improving access to care — a vital piece of the puzzle in addressing barriers to adequate prenatal and gynecological care.

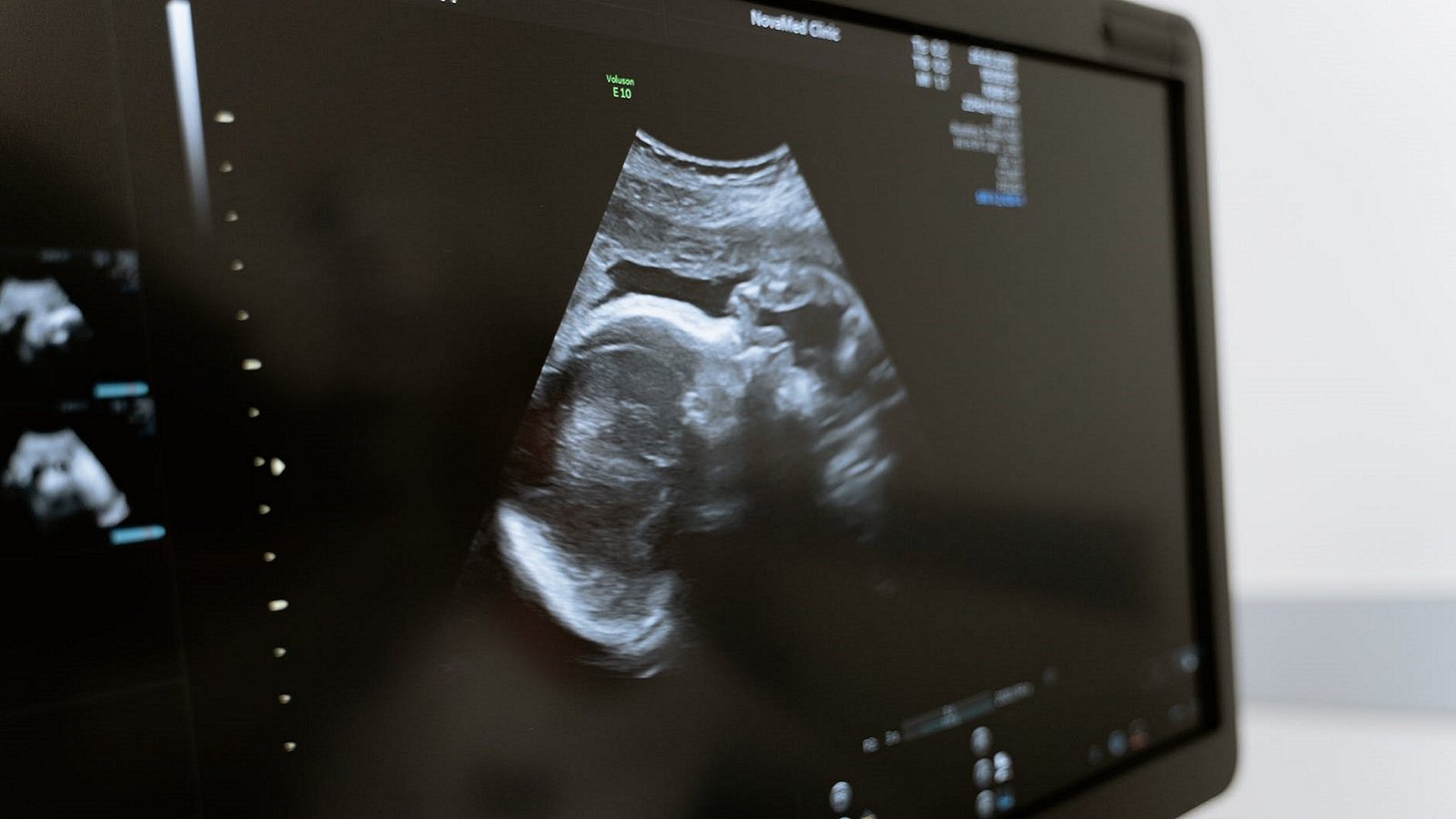

For more complex and at-risk obstetric patients, recent advancements in telehealth have made consultations with maternal fetal medicine specialists even easier and more accessible. Federal grants have provided funding for ultrasound technology that allows physicians to observe remotely, meaning a maternal-fetal-medicine doctor in St. Louis or Cape Girardeau, Missouri, could save a pregnant patient a six- to eight-hour round trip. Dr. McSpadden can feel more comfortable referring to these providers knowing that there are programs in place to assure the patient has minimal barriers to attending an appointment. It’s one more step to improving maternal and infant mortality for some of the state’s most vulnerable patients.

McSpadden and Missouri Highlands is just one example of how providers have worked to combat rural health disparities in the face of sluggish state governments. As rural hospitals continue to close doors, patients lose access to vital care — particularly vital prenatal care and perinatal care. But programs such as those mentioned above are picking up the slack to diminish the barriers of geographic isolation, the impact of the opioid crisis, and a physician shortage. Rural health continues to face unique problems that will require unique solutions, and it will take passionate providers like McSpadden to address these issues head-on.

**Feature photo by MART PRODUCTION from Pexels

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Jane Kielhofner is an MD Candidate at Harvard Medical School, where she serves on the Student Council as a Society Representative. She is also an active member of Medical Students Offering Maternal Support (MOMS) and Further Advancing Rural Medicine (FARM). Her current research centers on mitigating bias in medical education assessments and improving the transition between medical school and residency. In 2019, Jane graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree in Public Health from the University of Missouri-Columbia (Mizzou). While there, she also studied Constitutional Democracy through the Kinder Institute as an undergraduate Scholar and Fellow.

- Share

-

Permalink