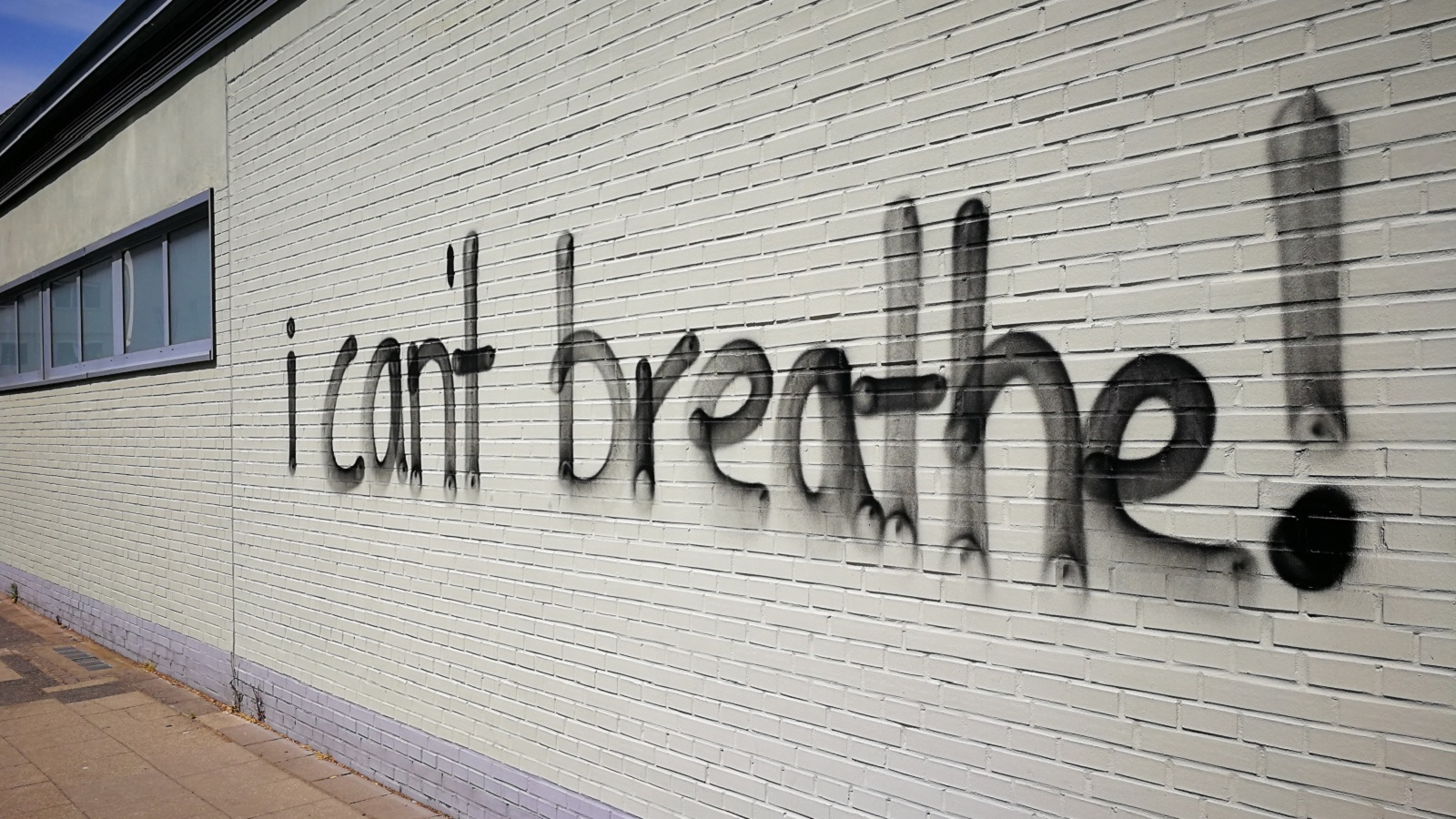

The racial equity movement and COVID-19 are bringing needed public attention to the structural racism and inequities that underlie social and health disparities in the United States. The police killings of George Floyd and so many other Black lives have brought about increasing calls for police reform. In Minneapolis, where George Floyd’s killing occurred, the City Council recently approved a proposal to disband their police department and replace it with a new Department of Community Safety and Violence Prevention. This increasing attention and action on structural racism is occurring across systems—in criminal justice, housing, education, and healthcare.

U.S. healthcare has a history of systematic abuse of African Americans, from J. Marion Sims, the “father of gynecology,” who experimented on enslaved women to the Tuskegee Syphilis study, which is today used as a prime example of unethical research. Racial disparities persist in healthcare with Black patients facing higher rates of infant and maternal mortality, premature death from stroke and heart disease, diabetes, and hypertension. COVID-19 has laid bare and worsened these disparities. Black, Hispanic, and Native American populations are being hospitalized at 4-5 times the rate of white populations due to pre-existing health disparities and other systemic inequities—living in densely populated areas that don’t allow for physical distancing, reliance on public transport, over-representation in prisons, and making up the bulk of essential workers.

COVID-19 has also revealed areas where the U.S. healthcare system is vulnerable. The sufficiency of the primary care workforce—in number, distribution, and financial stability—impacts access to care and health outcomes during COVID-19. The ability of these practices to recover post-COVID will have long-term effects, particularly for rural and underserved communities. The healthcare system has also demonstrated it is unprepared to care for its own workers, with widespread PPE (personal protective equipment) shortages and, further, healthcare workers facing reprimand or job termination for speaking out.

COVID-19 has demonstrated the destruction that happens when long-standing inequity is allowed to continue. This is now a time to reconsider the status quo. Racism and inequities are being confronted on the national stage, and health professions education is not immune.

The training pipeline influences primary care and underserved practice choices, defines the diversity of the health workforce and the experience of inclusion or discrimination by trainees, and sets the expectations and core skillsets of future health professionals. In the face of COVID-19, imagine a workforce skilled and empowered to address structural inequities—whether that be hospital preparedness, primary care access, or health disparities. Imagine a workforce on track to achieve national recommendations to increase the percentage of primary care physicians to 40%, far beyond medical schools’ current primary care output, which may be as low as 22%. This is social mission—the contribution of a school in its mission, programs, and the performance of its graduates, faculty, and leadership in advancing health equity and addressing the health disparities of the society in which it exists. There are points of light across the country:

- The Sophie Davis Biomedical Education Program is a seven-year BS/MD program at the CUNY School of Medicine. The program was founded in 1973 to create a pipeline for inner-city New York youth with a focus on creating primary care physicians. Students complete their undergraduate degree in three years and then are admitted to the CUNY School of Medicine without requiring the MCAT, a test with known racial differences.

- Frontier Nursing University has been using a community-based, distance education model since 1991 to meet their mission to train nurse midwives and nurse practitioners for diverse, rural, and underserved populations.

- A.T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona places medical students at community health centers in medically underserved areas around the country for three of the four years of undergraduate medical education.

- The U.S. Health Justice elective at the Yale School of Medicine is a student-led course to equip medical, nursing, and physician assistant students to provide effective care for minority populations.

- Brigham and Women’s Hospital Department of Medicine created a Health Equity Committee that partnered with existing community organizations to explicitly name racism, measure health disparities in their healthcare delivery system, and increase education around medical racism.

These programs and others are best practices in social mission. However, the question remains—why are these programs the exception and not the rule?

Schools are beginning to create curricula around health equity and racism, but too often, these courses are elective and not mandatory. Programs focused on community-based primary care, rural or underserved practice, and supporting students from underrepresented minorities and disadvantaged backgrounds are often dependent on grant funding. Furthermore, these programs are often supported by Black trainee time and labor. Black students and faculty are increasingly reporting exhaustion over the “minority tax,” which tasks underrepresented students and faculty to lead all calls for change, chair only diversity and inclusion committees, and educate their peers on these issues. Students are acting as subject matter experts on race and inequity for institutions with the means to hire full-time experts on these issues.

COVID-19 and the racial justice movement aren’t uncovering anything new. However, they are refocusing the spotlight on the need for systemic and institutional change. Students across the country are calling for racial equity reform, and it is not enough to simply admit there is a problem. Change will require full engagement of academic leadership, core institutional funding and resources directed to social mission priorities, valuing the contributions of minority students and faculty, and measures to ensure transparency and accountability. This time of upheaval is a time for health professions education to acknowledge the part we play in upholding systemic racism and to redefine what is truly important in the education of trainees. The time for social mission is now.

**Feature photo by ksh2000 from Pexels

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Autumn Nobles completed her undergraduate education at the University of Georgia and is currently a medical student at the Yale School of Medicine. She is an intern with the Beyond Flexner Alliance during summer 2020. Autumn is interested in the inclusion of social mission in health professions education, as well as racial and socioeconomic health disparities from a domestic and global lens.

Candice Chen, MD, MPH, is the Chair of the Beyond Flexner Alliance Board and Associate Professor of Health Policy & Management at the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity in the Milken Institute School of Public Health at The George Washington University. Prior to her current role, she was the Director of the Division of Medicine and Dentistry in the Bureau of Health Workforce at the Health Resources and Services Administration.

- Share

-

Permalink