A nine-year-old girl in London died from an asthma attack in 2013, and she is the first person in the world to have “air pollution” listed as a cause of death. And as we consider the COVID-19 pandemic, there are important lessons here for myriads of cities throughout the world.

A case report: Louisville

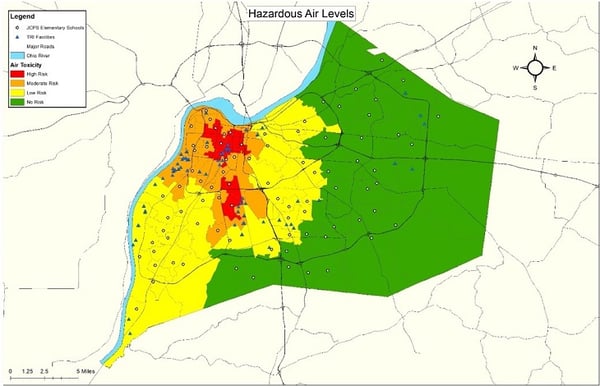

Let’s take the case of Louisville, Kentucky—one of the nation’s unhealthiest, and most polluted, cities. The basic problem? It’s the proximity of Louisville residents to industrial polluters: chemical industries, coal-fired energy plants, distilleries, and more.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), asthma, COPD, heart disease, and liver disease are up to four times higher for residents living near the city’s chemical factories compared to residents living in the Louisville metropolitan area (and further from the factories). Moreover, our research team recently found that Louisville ranks second worst in the United States for deadly toxic air when compared to 146 mid-sized U.S. cities. Strikingly, West Louisville residents are exposed to 84,699 tons of toxic air per year compared to just 7,320 tons in Bowling Green—one of the nation’s cleanest cities, located just 113 miles south of Louisville. In fact, Louisville air ranks worse than several well-known places for environmental degradation: Detroit’s smokestacks, Flint’s water, and Louisiana’s cancer alley.

The Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program was created by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. The TRI Program tracks the management of certain toxic substances that put human health and the environment at risk. TRI toxic chemicals cause chronic human health effects, such as cancer or chronic respiratory illness, and/or have significant adverse impacts on the environment.

The Toxics Release Inventory (TRI) Program was created by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) through the Emergency Planning and Community Right-to-Know Act. The TRI Program tracks the management of certain toxic substances that put human health and the environment at risk. TRI toxic chemicals cause chronic human health effects, such as cancer or chronic respiratory illness, and/or have significant adverse impacts on the environment.

Despite reliable data from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), the Louisville Air Pollution Control District continues to claim that Louisville’s level of pollution is “safe” for its residents. However, our research team analyzed data from the EPA, CDC, and Jefferson County Public Schools comparing quality of life in heavily polluted West Louisville to East Louisville, along with near and far clean air cities nationwide.

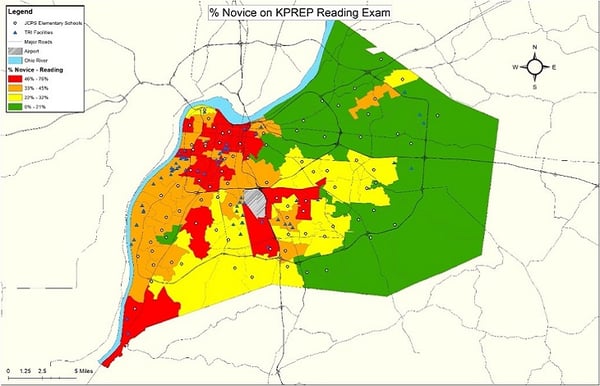

Jefferson County Public Schools provided us with proficiency scores in reading and math for elementary school students near and far from Rubbertown—a neighborhood that’s home to many chemical industrial plants. And a striking correlation we discovered is that elementary school students living nearer to industrial polluters perform less well in reading and math (with reading proficiency depicted visually by the following map):

Data from the Kentucky Performance Rating for Educational Progress (KPREP) assessment provided by Jefferson County Public Schools Open Datasets Data Portal

Data from the Kentucky Performance Rating for Educational Progress (KPREP) assessment provided by Jefferson County Public Schools Open Datasets Data Portal

Moreover, pollution shortens lives. Research shows that West Louisville residents die 10-12.6 years prematurely and that this is primarily due to toxic pollutants in the air, soil, and water.

Unfortunately, in Louisville, lobbying and million-dollar donations from chemical industries, coal-fired energy plants, and distilleries resulted in the sudden closure of environmental justice programs at the University of Louisville—the Kentucky Pollution Prevention Center and Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods. These environmental justice programs were replaced with an industry-funded center at the University of Louisville, the Christina Lee Brown Envirome Institute. This new center has posted numerous press releases on its website that ignore the negative effects of pollution and make false claims that levels of pollution in Louisville are improving.

Pollution & the COVID-19 pandemic

Our study of 146 mid-sized U.S. cities also demonstrates that cities with high levels of pollution have much higher COVID-19 case rates and deaths. The authors of this study argue that a contributing factor to this disparity is that persons living in highly polluted cities, especially in neighborhoods near industrial polluters, have higher rates of asthma and COPD, ultimately making them more vulnerable to severe complications from COVID-19 infection.

Now, let’s consider New Zealand—a country which currently reports fewer than 30 deaths from COVID-19, among approximately 4.9 million residents. In addition to Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern’s stellar leadership throughout the pandemic, instituting critical public health measures, we believe another key factor is that New Zealand is ranked in the bottom tenth percentile in the world for levels of air pollution, among 189 countries.

Moving forward

Reducing pollution will ultimately reduce health disparities, largely through improved housing, fewer chronic health conditions, fewer cases of COVID-19, and longer (and better quality) lives. One solution is to regulate cities’ levels of toxic air pollution, which may include moving industrial polluters out of residential areas. Of course, pollution is not the only factor creating such enormous health disparities, but it is one that many city leaders have ignored.

When a nine-year-old girl in London is declared dead from air pollution, it makes us wonder how many more children are also being harmed. In the words of Larissa Lockwood, Director of Clean Air at Global Action Plan, “Children have the right to breathe clean air. As our Clean Air Day research showed, air pollution doesn’t just affect a child’s health, but can also affect their working memory and hence their ability to learn. To safeguard the future of our children’s health and educational potential, we need to work together to take urgent actions […] to eliminate harmful pollutants.”

Acknowledgements: We are grateful for assistance from University of Louisville students, Lily Z. Stewart, Sarah Rionn Blalock, and Jeremy Chesler; three additional students who interned with the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under President Donald Trump; one student who works in the same building as the Louisville Air Pollution Control District; and a former student who works for the state of Texas as a public health official.

**Feature photo by Johannes Plenio on Unsplash. Both map images were created by author Isaiah Kingsberry for the purposes of this publication.

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our bi-weekly newsletter

Interested in contributing to the Harvard Primary Care Blog? Review our submission guidelines

John I. (Hans) Gilderbloom, PhD, is a Professor in the Graduate Planning, Public Administration, Sustainability, and Urban Affairs program at the University of Louisville, where he also previously directed the Center for Sustainable Urban Neighborhoods. Dr. Gilderbloom has published widely, and his research has appeared in numerous books, academic journal articles, monographs, and opinion pieces.

Isaiah Kingsberry is a Graduate Research Assistant in the University of Louisville Department of Geography & Geosciences. A Woodford R. Porter Scholar recipient and National Science Foundation research participant, Isaiah's research aims to close the gap between our physical and experienced environments.

Isaiah Kingsberry is a Graduate Research Assistant in the University of Louisville Department of Geography & Geosciences. A Woodford R. Porter Scholar recipient and National Science Foundation research participant, Isaiah's research aims to close the gap between our physical and experienced environments.

Gregory D. Squires, PhD, is a Professor of Sociology and Public Policy & Public Administration at The George Washington University. He currently serves as a member of the Fair Housing Task Force of the Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights, the Social Science Advisory Board of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council in Washington, D.C., and the Board of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in D.C. He has published widely in the academic literature, and his recent books include the following: Meltdown: The Financial Crisis, Consumer Protection, and the Road Forward; and edited book, The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences, and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act.

Gregory D. Squires, PhD, is a Professor of Sociology and Public Policy & Public Administration at The George Washington University. He currently serves as a member of the Fair Housing Task Force of the Leadership Conference on Civil & Human Rights, the Social Science Advisory Board of the Poverty & Race Research Action Council in Washington, D.C., and the Board of the Duke Ellington School of the Arts in D.C. He has published widely in the academic literature, and his recent books include the following: Meltdown: The Financial Crisis, Consumer Protection, and the Road Forward; and edited book, The Fight for Fair Housing: Causes, Consequences, and Future Implications of the 1968 Federal Fair Housing Act.

- Share

-

Permalink