In the 1980s, a set of historical city maps resurfaced to reveal a hidden facet of our neighborhoods—the redlined status. As it turns out, the implementation of these maps saved the housing sector and bolstered prosperity for some demographic groups but increased disparities in homeownership, wealth, and health for others.

The structural inequalities set in place by federal policies over 80 years ago are still evident in communities today. As our nation continues to fight the COVID-19 pandemic, the historic designations of a neighborhood between “hazardous” and “best” continue to parallel inequities in testing, case rates, fatalities, and vaccinations. These historic lessons shine a light on the importance of explicitly including an equity lens for current policy decisions, not only to address current disparities, but the lasting effect decades later.

How did we get here?

In 1933, President Roosevelt created the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) with the goal of bolstering a failing housing market during the Great Depression. The plan was to refinance home mortgages and expand home buying opportunities for Americans.

In order to do this, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation evaluated over 200 cities in the U.S. for neighborhoods of “mortgage security,” using data from local lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers. Each city’s neighborhood was graded on a four-level system:

- A, lined in green, was “best,” with a low perceived risk for lenders;

- D, lined in red, was “hazardous,” with a high perceived risk for lenders—these areas formed the basis for the term “redlining.”

When classifying neighborhoods, evaluators didn’t just look at current housing quality and rent and sale values, but also the color of the residents’ skin. In Birmingham, Alabama, an area with “executives, businessmen, and retired professional men” was graded as “best” with an A rating, while an adjacent neighborhood described as a “negro low-cost slum clearance project” was redlined with a D grading.

HOLC grades were then adopted by private and public entities and became an essential component of housing sector decisions up until the 1970s. Over the course of these decades, the practice of redlining stymied the ability of residents in redlined areas—most of whom were Black Americans—from building wealth by restricting home ownership and appreciation of home values.

How redlining harmed health

With 89% of health explained by factors outside of medical care, careful attention should be paid to the environment and social circumstances in which people live. Several studies show that living in redlined areas has been linked to severe asthma, birth outcomes, cancer stage at diagnosis, urban heat, and food environments, among other present day adverse effects.

Many of these health conditions also place individuals at increased risk for COVID-19. COVID-19 comorbidities are more prevalent among communities of color, and these populations exhibit higher exposure, positive tests, hospitalization, and death rates in comparison to white populations.

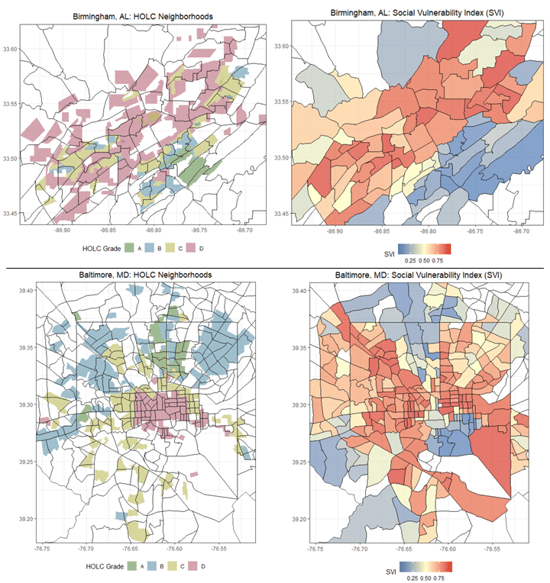

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Social Vulnerability Index (SVI) scores the susceptibility of communities to disasters or disease outbreaks, such as COVID-19. When comparing redlined maps of Birmingham, Alabama to current maps of social vulnerability scores, there is a clear relationship between redlined areas and socially vulnerable areas, emphasizing redlining’s impact on present day adverse health outcomes.

Figure 1: Data from Mapping Inequality and CDC

Redlined neighborhoods changed by gentrification

Redlining also creates conditions for gentrification, which results in changes to the characteristics of neighborhoods and ultimately has mixed effects on the health of residents.

For example, the HOLC maps of Baltimore (shown in Figure 1) look like a target with concentric rings of improving grades moving outward—and the bullseye is the formerly redlined region. The current SVI map also shows similar patterns of vulnerability to prior HOLC grades. Upon further investigation, there is a subregion within the redlined center that displays surprisingly low vulnerability. That subregion of Baltimore has been subject to a modern form of displacement known as gentrification.

Gentrification is the influx of higher-income, more educated, and mostly white residents into a traditionally low-income, minority neighborhood. Gentrification may increase access to physical and institutional improvements like grocery stores over mini-marts, public parks over empty lots, or coffee shops over liquor stores. While these changes can improve the living conditions and amenities of neighborhoods, they come at higher costs of living and are not equally accessible to all residents, especially low-income and racial/ethnic minorities.

Why do communities gentrify? Historically redlined areas often exhibit a “rent gap”—the difference between the potential value of the property and the current prices of housing. The prime location of urban housing paired with historical underinvestment and low rent prices make them attractive to young career professionals, developers, and investors looking to capitalize on the gap in property values. In San Francisco, 87% of neighborhoods undergoing gentrification were once redlined as “hazardous.”

Secondary effects of gentrification on health

For legacy residents who remain in their communities, gentrification may lead to new investments and economic opportunities, improving social conditions and health outcomes. However, the higher cost of living, stress, and anxiety from cultural displacement can negate that impact.

Legacy residents who are displaced face tremendous housing instability. Those who find new homes tend to move to similar socioeconomic neighborhoods as their previous community. The costs and stressors associated with moving as well as the disruption to social networks and community ties ultimately lead to negative health outcomes. Recent social connections research shows that limited networks cause greater detriment to health than obesity, smoking, and high blood pressure and increase susceptibility for anxiety and depression.

Additionally, areas undergoing gentrification see an expansion in police presence. While police may signal increased safety for new residents, multiple studies have shown that police interactions have significant associations with poor mental health outcomes, particularly for Black Americans. Recent evidence from a longitudinal study of gentrification in New York notes a trend of increased 311 calls and discretionary arrests, of which young men of color are the primary target.

Acknowledging redlining and gentrification in the era of COVID-19

It is no surprise that COVID-19 has disproportionately affected low-income and minority communities. The U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey has been capturing the status of social and economic impacts of the pandemic. The evidence suggests that housing disparities are further widening by race and income, with Black and Latino renters more likely to miss rent compared to white renters and Black homeowners more likely to defer mortgage payments compared to other groups.

Furthermore, these same groups experience higher incidences of COVID-19, even on a community scale. With the combined pressure from economic and geographical influences, the situation becomes a double-edged sword, exacerbating the disparities in health outcomes especially for minority populations.

Redlining resulted from a federal policy in response to a housing crisis but worsened health disparities for minority communities to this day. As the nation moves forward from this global pandemic, the response through policies and implementation must keep a health equity lens at the forefront to remedying missteps from the past and avoid the same path for the future. The explicit focus from the Biden Administration on advancing health equity is not only essential now to ensure vulnerable populations have equal access to testing, care, and vaccinations in the near future, but also on the health impacts down the line.

About the authors

Hannah De los Santos, PhD, MS, is a Senior Data Scientist in the Model-based Analytics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned her PhD in Computer Science and her MS in Applied Mathematics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Her work seeks to use data analytics techniques to solve problems in health.

Karen Jiang, MPH, is a Domain Specialist in the Clinical Quality and Informatics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned her MPH in Health Policy from Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Her interests lie at the intersection of health policy, health equity, and data analytics.

Karen Jiang, MPH, is a Domain Specialist in the Clinical Quality and Informatics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned her MPH in Health Policy from Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Her interests lie at the intersection of health policy, health equity, and data analytics.

Julianna Bernardi, BS, is an Associate Data Scientist in the Model-based Analytics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned a Bachelor’s of Science from Wentworth Institute of Technology in Applied Mathematics. She is interested in using mathematics and data visualizations to tell stories and facilitate work in the public interest.

Julianna Bernardi, BS, is an Associate Data Scientist in the Model-based Analytics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned a Bachelor’s of Science from Wentworth Institute of Technology in Applied Mathematics. She is interested in using mathematics and data visualizations to tell stories and facilitate work in the public interest.

Cassandra Okechukwu, ScD, MSN, MPH, is a Principal Health and Life Scientist at The MITRE Corporation. She is a social epidemiologist with over 15 years of experience in healthcare and public health. Dr. Okechukwu’s chief expertise is using knowledge from social and behavioral sciences to inform the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs, policies, and technologies that promote population health.

Cassandra Okechukwu, ScD, MSN, MPH, is a Principal Health and Life Scientist at The MITRE Corporation. She is a social epidemiologist with over 15 years of experience in healthcare and public health. Dr. Okechukwu’s chief expertise is using knowledge from social and behavioral sciences to inform the design, implementation, and evaluation of programs, policies, and technologies that promote population health.

**Feature photo by Maria Orlova from Pexels

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Interested in contributing to Perspectives in Primary Care? Review our submission guidelines.

- Share

-

Permalink