Mental health is a growing public health priority. While people from racial/ethnic minority groups generally report a similar prevalence of mental health conditions compared to the rest of the U.S. population, they have poorer access to mental health services, and there is evidence of potential emerging disparities.

Good mental health is more than the absence of a condition or illness—it means that we can thrive and have opportunities to flourish. Our mental health is impacted by social determinants of health, including where we live. The physical places and environments where we live affect our ability to access resources and the obstacles we face when it comes to achieving good mental health.

Things like quality housing and access to amenities, feeling safe in our neighborhood, trees, and places to relax and play outside, places to gather and feel included, and a sense of belonging all contribute to our mental health. Differential experiences for racial/ethnic groups can contribute to mental health outcomes in both positive (e.g., cultural identity) and negative (e.g., microaggressions) ways.

Exposure to poverty and/or experiences of residential discrimination and structural racism directly contributes to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), which increase the risk of negative mental health outcomes such as suicide attempts and illicit drug use. Experiencing six or more ACEs equates to a reduction of 20 years of life expectancy.

New research by our team is shaping our understanding of how discriminatory housing policies of the past can impact present-day mental health, and how current policies may be perpetuating disparities.

Residential Discrimination and Health

The discriminatory practice of classifying certain neighborhoods as unworthy of investment due to the racial/ethnic makeup or economic or immigration status of residents is known as redlining. Historic redlining is just one form of residential discrimination and has present-day impacts on the health and wellbeing of the people who were excluded from the same kind of investments that helped white middle- and upper-class families build intergenerational wealth. There is a growing body of literature that points to the association between historic redlining policies and present-day health outcomes and racial/ethnic health disparities.

Take Baltimore, for example. Throughout the early 19th century and even after the Civil War, Baltimore was not racially segregated. Following the Great Migration that brought an influx of Black populations into Baltimore from the south, crowded housing conditions, and white flight. In 1910, Baltimore passed a city ordinance aimed at preventing Black people from living anywhere near white people. Although the Supreme Court deemed housing segregation laws unconstitutional in 1917, Baltimore city government and private entities persisted in enforcing similar policies through the use of discriminatory covenants and housing ordinances, widespread tools for housing discrimination used nationwide throughout the 20th century.

|

|

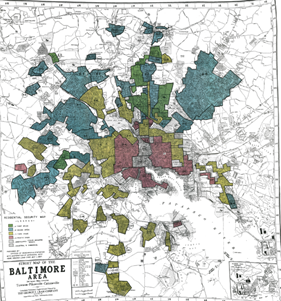

Figure 1. Original HOLC Map of Baltimore Area from Mapping Inequality |

Twenty years later, the Federal Housing Administration and Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) created maps across the nation that evaluated the mortgage security risks in neighborhoods, frequently grading areas with racial/ethnic minority residents as “hazardous.” In Baltimore, the HOLC maps reinforced the previous discriminatory practices and classified areas of Baltimore that its leaders, lenders, and real estate brokers saw as “appropriate” for white populations, as opposed to non-white and/or immigrant populations, as shown in Figure 1. As a result, people from racial/ethnic minority groups living in the “hazardous” red HOLC areas of Baltimore were deemed ineligible for loans and were excluded from the public and private capital that allowed many White people to become homeowners and pass property on to their children.

The relationship between historic redlining and mental health is still emerging in the literature: if you live in an area that was graded as “hazardous” in the 1930s, are there modern impacts on your mental health? Our research team decided to analyze the relationship between the historic HOLC grades and present-day data on poor mental health from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention across 63 US cities. We did a closer analysis specifically of Baltimore.

|

|

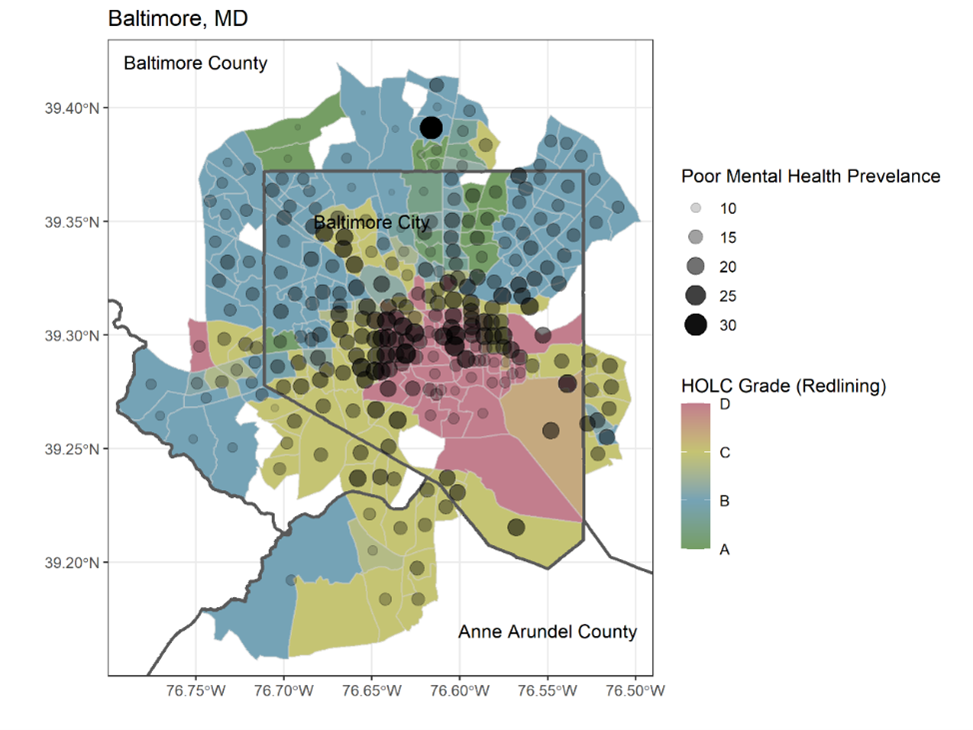

Figure 2. Baltimore Area HOLC Grades by Census Tract and Poor Mental Health Prevalence from MITRE |

The Link to Mental Health in Baltimore

In present day Baltimore, neighborhoods with lower historic HOLC grades had higher percentages of their community who reported more than two weeks of poor mental health days each month. This pattern remained even after taking into account other possible factors, like poverty, unemployment, education, housing stress, residential segregations, and other demographic factors. Next, we took a deeper dive to understand how neighborhood context and change can impact this relationship.

Baltimore has a majority of non-white residents, with 58 percent of the population identifying as Black or African American, and 28 percent identifying as non-Hispanic white. We examined whether this association between HOLC grades and poor mental health prevalence held true in a subset of neighborhoods with the largest non-white populations.

This closer look revealed differences in poor mental health prevalence in historically redlined areas where residents have been displaced by wealthier, whiter populations (known as gentrification) versus redlined areas that continue to experience disinvestment and have a larger share of non-white residents. Historically redlined areas that received more modern-day financial investments, like the downtown area or Inner Harbor of Baltimore, and where there are a greater share of white people today, reported better mental health outcomes. A 2020 analysis of investment flows in Baltimore shows that neighborhoods with higher poverty and a majority of Black residents received dramatically less investment. While there is a demonstrable relationship between HOLC-grades on mental health outcomes, modern-day lending and investment disparities between white and Black and rich and poor communities can confound this relationship.

Taking it Back to the Present

Modern-day, upstream factors related to neighborhood change and investment levels appear most likely to impact the association between HOLC grade and poor mental health prevalence. While the Fair Housing Act outlawed housing discrimination, it still happens in practice through inequitable lending and investment. Structural racism didn’t end with 1930s discriminatory HOLC policies.

Modern day residential discrimination takes many forms. Lending disparities for applicants identifying as racial/ethnic minorities are present in mortgage data, a measure in the Mental Wellness Index that can be stratified for Black populations. Black homeowners, for example, often experience undervaluation of their homes during appraisals. In one notable case in Baltimore, a Black family’s home was initially valued at $472,000. After removing family photos and having a white male colleague stand in during a second appraisal, their home was valued at $750,000. Black homeowners are also disproportionately targeted for reverse mortgages (noted by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau to be complex products that are difficult for consumers to understand in light of misleading advertising, risk of fraud, and other scams). Despite the recent record gains in overall homeownership rates, Black homeownership is declining and is lower than it was a decade ago. The average Black homeowner owes more in mortgage debt than their White counterparts on a house with less value.

Encouragingly, the Justice Department announced an initiative to combat modern-day redlining in October 2021. The result has been a number of settlements with mortgage institutions, like the $20 million dollar settlement with Trident Mortgages in Philadelphia for discouraging people from racial/ethnic minority groups from applying for home loans.

These realities of modern-day residential discrimination serve as a reminder that the social determinants of health are not static data points. They are dynamic factors impacting our mental health and well-being. Neighborhoods’ history, including past residential discrimination and present-day investment levels, affect the people that reside there. These factors impact residents’ ability to generate income and build wealth, their financial stability, and, ultimately, their opportunities to thrive and have good mental health. Neighborhood experiences, history, and context in the places we live matter for our mental health.

About the authors

|

Emilie Gilde, MPP, is an Evidence-based Policy Analysis and Design Group Lead at The MITRE Corporation who led the Mental Wellness Index team as part of MITRE’s Social Justice Platform. Prior to MITRE, Emilie was the Director of Health Policy and Promotion at Baltimore City Health Department and a Peace Corps Volunteer in Lesotho. Emilie has an MPP from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County where she also served as a Shriver Peaceworker Fellow. |

|

Elizabeth Murphy, MPH, is a Health Policy Lead at The MITRE Corporation. Prior to MITRE, Elizabeth was a Policy and Advocacy Advisor at Jhpiego, a Johns Hopkins University-affiliated global health non-profit. She also previously served as Director of Coalitions and Outreach at the Coalition for Public Safety, a national bipartisan effort to advance criminal justice reform. Elizabeth has a Master of Public Health from Vanderbilt University. |

|

Karen Jiang, MPH, is a Health Equity Analyst in the Clinical Quality and Informatics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned her MPH in Health Policy from Harvard T. H. Chan School of Public Health. Her interests lie at the intersection of health policy, health equity, and data analytics. |

|

Hannah De los Santos, PhD, MS, is a Lead Data Scientist in the Model-based Analytics Department at The MITRE Corporation. She earned her PhD in Computer Science and her MS in Applied Mathematics from Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. Her work seeks to use data analytics techniques to solve problems in health. |

**Feature photo obtained with a standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our newsletter.

Interested in contributing to the HMS Primary Care Review? Review our submission guidelines.

- Share

-

Permalink