Every day in the hospital, and during every visit to the clinic or emergency room, we pay scrupulous attention to your vital signs: heart rate, temperature, respiratory rate, and blood pressure. These numbers are the bedrock of understanding what is happening with a patient’s health. We should add another number to this group: the Adverse Childhood Event (ACE) score.

The significance of Adverse Childhood Event (ACE) scores

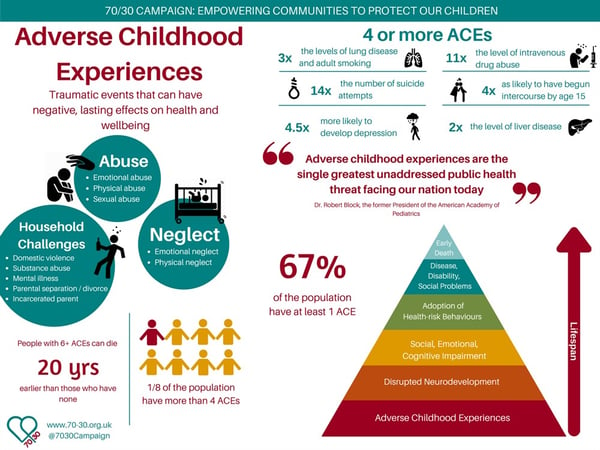

The ACE score was developed in California in the 1980s and ‘90s and is based on a series of survey questions about one’s life from birth to 18 years old. These questions assess a range of potential childhood traumas, including intimate partner violence, neglect, household substance use disorder, parental separation, and physical, emotional, and sexual abuse.

ACE scores seem to have a direct relationship with an enormous variety of mental and physical health outcomes. For example, compared to those with an ACE score of 0, those who have an ACE score of 4+ were found to have 4- to 12-fold increased health risk for alcohol and substance use disorder, depression, and suicide attempts; they were also much more likely to be diagnosed with cancer, develop emphysema, marry an alcoholic, have strokes and heart attacks, and have shorter lives. Though the idea may be intuitive, the actual data is shocking.

WAVE Trust and the 70/30 Campaign

ACE score qualification as a vital sign

Because early childhood trauma is so important to later health, it needs to be accounted for in medicine. Calling ACE scores a vital sign may be a provocative suggestion, but it is not without merit nor precedent. In fact, everything from oxygen saturation to menstrual cycles to pain have been proposed as additional vital signs.

A vital sign is an easily assessed number which gives general diagnostic and prognostic information about the body and its functions. Vital signs don’t instantly give a diagnosis, but they do provide important information which allows clinicians to recognize constellations of effects and patterns.

As any clinician knows, low blood pressure and a fever makes you worry about a serious bloodstream infection. Likewise, a fast heart rate and fast breathing rate makes you suspicious that your patient had a large blood clot from their legs which dislodged and went to their lungs. Low blood pressure and fast heart rate may mean a heart attack (or just dehydration).

Vital signs are not just numbers; they tell stories. They hint in a general way where a patient has been, is now, and where they’re going. If this is true, then ACE scores certainly fit the bill – especially because trauma, while social, is an embodied and physiologic reality.

Integrating ACE scores into a community primary care clinic

In a primary care setting, it is important for clinicians to have a general sense of how past trauma affects present health. Currently, the topics on ACE survey questions are occasionally, but not routinely, assessed by medical systems. For clinicians, this may be out of a surplus of tact, lack of time, the potentially disturbing nature of the topics, or unease about how to react when there is nothing immediate to be done (the “Pandora’s box” effect).

In the University of Minnesota community primary care clinic at which I am currently a medical student, we are trying to implement a novel process in the Electronic Health Record. We propose the following: As patients arrive for their appointment and fill out new-patient intake information on tablets, they are prompted to fill out an opt-out ACE questionnaire. It is important that this is a private process and the sensitive questions not be asked by the rooming staff, as this may influence answers patients give. Once completed, the final score (not the individual item responses) is presented in the general patient information alongside demographic information, vitals, and health maintenance prompts. In addition, clinic staff and clinicians will be given didactic information about ACE scores and how to appropriately understand and interpret their meaning.

The challenges and dangers of using ACE scores

Even if it is worth doing, are there dangers in using ACE scores in this way? Certainly so. We must be careful not to use ACE scores to stigmatize patients. We also must realize that trauma is a deeply personal, social, psychological, and existential reality: its truest meaning cannot be expressed in a number, even if the anonymized nature of it provides a level of security and distance.

We must also be careful to recognize all forms of trauma correctly. In the original study, participants and questions were overwhelmingly white-centric and middle class; thus, newer metrics like the Philadelphia Expanded ACE survey make a point to also ask about experiences of racism, bullying, foster care, and having been a witness to violence. A measurement tool such as this must not presume perfect objectivity, but maintain a measure of revisability and epistemic humility in light of changing understandings.

Finally, because trauma itself is an experience of “disempowerment and disconnection,” we must be careful not to use ACE scores in such a way as to further isolate and disempower our patients by implying that history is destiny.

The benefits of ACE scores and increased trauma awareness

Though the research is still ongoing, anecdotal experience suggests that learning about ACE scores is often a liberating experience for patients – many feel as though they finally have an answer to unexplainable distress and suffering. In diseases like depression, learning about the complex (and malleable) interrelations of neurobiology, psychology, and society has been shown to increase agency, compared to messages emphasizing only a fixed biological origin This understanding then encourages reconnection and recovery, which are the key ingredients for healing from trauma.

As psychiatrist Judith Herman writes, recovery from trauma is the (re)creation of the capabilities for “trust, autonomy, initiative, competence, identity, and intimacy” through relationships with others. A focus on trauma teaches that the mind, body, and spirit are deeply intertwined and that healing must be a holistic enterprise. Healing trauma, and minimizing the effects of ACE scores, is indeed possible. Moreover, there is ongoing research into the protective factors and relationships that have come to be known as ‘counter-ACEs’ – an understanding that is also bolstered by the results of Harvard’s Grant Study, the longest-running study of adult development and flourishing.

A final benefit of increased awareness of trauma’s effects on health is the sociopolitical project it hints at a less trauma-inducing world. This is a life-affirming approach that is “political but not partisan” and one that all those who care for others, professionally or otherwise, can agree on.

A world of healthier people is one where children are safer, where we resist both fast and slow violence, and where all have the resources and relationships necessary to heal. It also becomes clear that so-called “bad choices” leading to poor health are actually primarily the fault of social and structural violence – this is freeing for patients but also leads to more empathy and engagement for providers. Taking ACE scores as seriously as blood pressure is a step towards healthier lives and a more livable world.

Acknowledgements: Brendan Johnson would like to thank Justin Rasmussen, PhD(c), and Brett McCarty, ThD, of Duke University for conversations on mental health, malleability, and the ACE score literature, as well as thanking Matthew Young, MD, and David Hottinger, MDiv, of Hennepin Healthcare for their pioneering work on trauma-informed care in a clinical context.

**Feature photo obtained with standard license on Shutterstock.

Interested in other articles like this? Subscribe to our monthly newsletter

Interested in contributing to the Primary Care Review? Review our submission guidelines

Brendan Johnson, MTS, is a student at the University of Minnesota Medical School and a graduate of the Duke Theology, Medicine, and Culture Fellowship. His work highlights the need for liberation in medicine and the inherent dignity of radical care for others. He can be found @dbrendanjohnson and co-hosts the podcast “Social Medicine On Air.” His other writing can be found at linktr.ee/dbrendanjohnson.

Brendan Johnson, MTS, is a student at the University of Minnesota Medical School and a graduate of the Duke Theology, Medicine, and Culture Fellowship. His work highlights the need for liberation in medicine and the inherent dignity of radical care for others. He can be found @dbrendanjohnson and co-hosts the podcast “Social Medicine On Air.” His other writing can be found at linktr.ee/dbrendanjohnson.

- Share

-

Permalink